Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Portrait of Mr. Blackburne, February 1811,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1640.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Portrait of Mr. Blackburne, February 1811,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1640.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

In this highly worked drawing made when John Smart was seventy years old, just three months before his death on May 1, 1811, the artist depicts a “Mr. Blackburne” in a dark coat and white stock: A type of neckwear, often black or white, worn by men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. tie highlighted with strokes of gouache: Watercolor with added white pigment to increase the opacity of the colors..1The name “Mr. Blackburne” has accompanied this piece through several historical sales; see the provenance section of this entry. For Smart’s death date, see The Gentleman’s Magazine 81, no. 1 (1811): 599, cited in Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 27. For more on the materiality of Smart’s drawings, see the “Technical Note,” by Rachel Freeman in “John Smart, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1786,” in this catalogue. The sitter is placed within a penciled oval trompe l’oeil: An art technique that tricks the eye, using realistic imagery to create the illusion of a three-dimensional object. frame, featuring carefully observed details such as his receding hairline and piercing blue eyes. Unlike Smart’s preparatory sketches, such as the portrait of Mr. Dickinson, also in the Starr Collection, this drawing is larger and more meticulously rendered, reflecting a new type of portrait that provided Smart’s clients with an ample yet more economical alternative to his ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. miniatures. This portrait is signed with the artist’s full name and the month and year of its production, February 1811, an unusually complete inscription that underscores the significance of this work for the artist.

While Blackburne (or Blackburn) is a common surname, one of the best-known individuals with that name was John Blackburne (1754–1833), who may be the sitter in the present portrait. Blackburne was an influential English landowner and a long-serving Member of Parliament (MP) for Lancashire. Educated at Harrow School and Oxford University, he succeeded to his family’s estates and was appointed High Sheriff of Lancashire in 1781. Blackburne served as MP for Lancashire from 1784 until 1830, aligning as an Independent and generally supporting William Pitt. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, Britain’s premier scientific society, in 1794. Blackburne distinguished himself in Parliament with several positions that went against the grain of public opinion to advocate for Lancashire matters.2Notably, in 1811, the year Smart realized this portrait, Blackburne voted against the government on the Regency Bill and supported efforts to reduce sinecures. He advocated for Lancashire matters, including inquiries into the cotton industry. Although an independent voice, he opposed Catholic relief and was recognized for his consistent resistance to its passage throughout his parliamentary career. Information about Blackburne’s political history has largely been drawn from M. H. Port and David R. Fisher, “John Blackburne (1754–1833),” The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1754–1790, ed. Lewis Namier and John Brooke (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), accessed September 22, 2024, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/blackburne-john-1754-1833. See also Margaret Escott, “John Blackburne (1754–1833),” The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1820–1832, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/blackburne-john-1754-1833#family-relations.

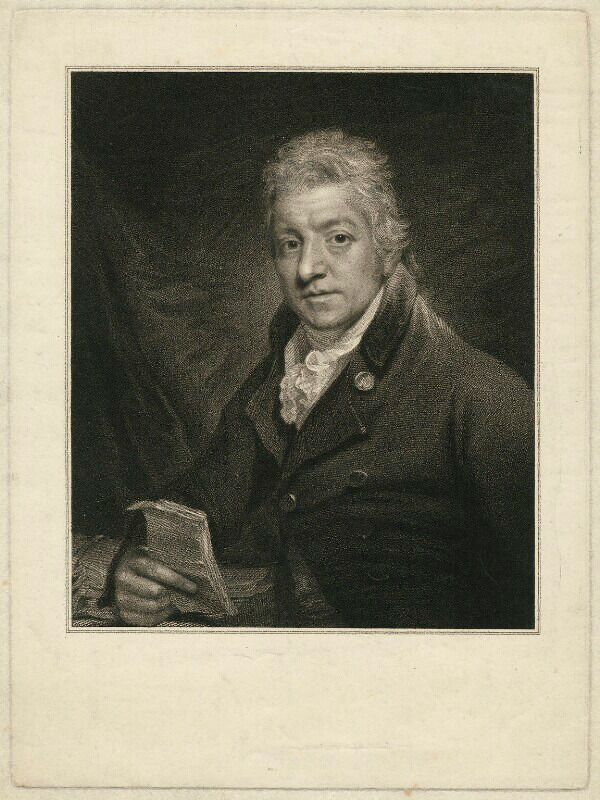

John Blackburne appears in several portraits by Smart’s near-contemporaries, including an early portrait by George Romney (1734–1802) from 1787, which, although highly stylized, shows the sitter’s distinctive blue eyes. A much later print after a portrait by William Beechey (1753–1839) (Fig. 1) shows Blackburne as an older man, with a receding hairline and features that more closely align with the individual in Smart’s portrait. If the sitter in Smart’s drawing is indeed John Blackburne, he would have been fifty-seven years old at the time, reflecting the more mature appearance captured by Smart.

It is also possible that the “Mr. Blackburne” depicted in Smart’s portrait is the same John Blackburn mentioned in an 1800 London newspaper notice detailing a theft from his property. Among the stolen items were “three miniature pictures,” suggesting that Blackburn may have had an interest in collecting miniatures. Although the accused was acquitted due to lack of evidence, the mention of these miniatures raises the intriguing possibility that Blackburn commissioned this work from Smart eleven years later.3I am grateful to Starr Research Assistant Maggie Keenan for sharing this newspaper record with me. See “Trial of Henry Roper,” October 29, 1800, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18001029-57?text=miniature.

In the absence of a corresponding ivory miniature, the present drawing stands as a singular and likely definitive portrayal of this “Mr. Blackburne.” The fact that many of Smart’s drawings were retained by his family and sold in the late 1930s, with no record of this particular work among them, adds to the rarity and significance of this portrait. Given its highly finished nature, unusual for a preparatory sketch, and its detailed signature, this work may have served as a special commission for Blackburne, perhaps marking a significant moment in his life, such as his political achievements in 1811. Whether or not the sitter is definitively John Blackburne of Lancashire, the drawing remains an exceptional example of Smart’s late work, blending meticulous technique with his keen ability to capture both the physical presence and character of his subject.

Notes

-

The name “Mr. Blackburne” has accompanied this piece through several historical sales; see the provenance section of this entry. For Smart’s death date, see The Gentleman’s Magazine 81, no. 1 (1811): 599, cited in Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 27. For more on the materiality of Smart’s drawings, see the “Technical Note,” by Rachel Freeman in “John Smart, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1786,” in this catalogue.

-

Notably, in 1811, the year Smart realized this portrait, Blackburne voted against the government on the Regency Bill and supported efforts to reduce sinecures. He advocated for Lancashire matters, including inquiries into the cotton industry. Although an independent voice, he opposed Catholic relief and was recognized for his consistent resistance to its passage throughout his parliamentary career. Information about Blackburne’s political history has largely been drawn from M. H. Port and David R. Fisher, “John Blackburne (1754–1833),” The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1754–1790, ed. Lewis Namier and John Brooke (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), accessed September 22, 2024, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/blackburne-john-1754-1833. See also Margaret Escott, “John Blackburne (1754–1833),” The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1820–1832, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/blackburne-john-1754-1833#family-relations.

-

I am grateful to Starr Research Assistant Maggie Keenan for sharing this newspaper record with me. See “Trial of Henry Roper,” October 29, 1800, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18001029-57?text=miniature.

Technical Note

Read more about the types of papers John Smart used at the associated technical note.

Provenance

Unknown woman, by November 2, 1971 [1];

Purchased from her sale, Important English and Continental Miniatures, Christie’s, London, November 2, 1971, lot 105, as Mr. Blackburne, by Asprey, 1971 [2];

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1973;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1973.

Notes

[1] According to the 1971 sales catalogue, lot 105 was the “Property of a Lady.”

[2] According to Art Prices Current (1971–72), Asprey bought lot 105 for £630.

Exhibitions

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Mr. Blackburne.

References

Important English and Continental Miniatures (London: Christie’s, November 2, 1971), 31, (repro.), as Mr. Blackburne.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 149, (repro.), as Mr. Blackburne.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.