Citation

Chicago:

Maggie Keenan, “John Smart, Portrait of Pulteney Malcolm, Captain of the Donegal, 1809,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1636.

MLA:

Keenan, Maggie. “John Smart, Portrait of Pulteney Malcolm, Captain of the Donegal, 1809,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1636.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

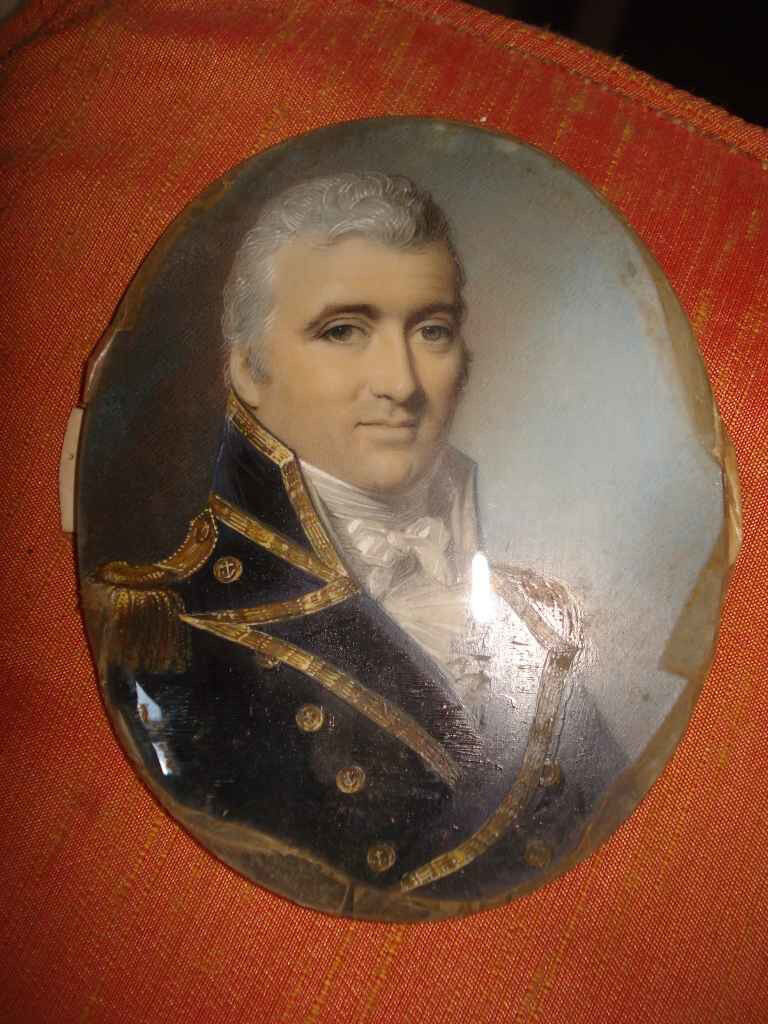

John Smart examines every aspect of the celebrated military figure Pulteney Malcolm (1768–1838) in this portrait miniature, from the gold braid of his uniform to his hazel eyes, scarred chin, and kind demeanor that even French enemy Napoleon Bonaparte noticed and appreciated. Malcolm was born on February 20, 1768, one of seventeen children of George Malcolm (1728–1803), a farm manager, and Margaret Pasley (1742–1811) in Douglen, Scotland; he was named after his parents’ landlord, Sir William Pulteney.1Paul Martinovich, The Sea is My Element: The Eventful Life of Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, 1768–1838 (Warwick: Helion, 2021), 18. Having come from a large family himself,2Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 18. George declared bankruptcy in 1780 because his side business of importing wine in the Canary Islands failed, which likely forced him to find professions for his four oldest sons. Malcolm’s father was desperate for financial assistance and enlisted his brother-in-law, Royal Navy Captain Thomas Pasley, to secure the employment of his young son, Pulteney Malcolm.3Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 19. Captain Pasley arranged for Malcolm to live at his sister’s house in Portsmouth, while also paying for his nephew’s additional schooling. A 1780 letter from George to William Pulteney documents these major life events: “My third Son who has the Honour to be your Name has been at an Academy for about a Year in the Neighborhood of South Hampton where Mr. Briggs [Pasley’s sister’s husband] now lives. He was there at the Expense of Captain Pasley. I have got from all his friends very flattering Accounts of his Progress. He is now going to Sea with his Uncle.” George Malcom to William Pulteney, February 11, 1780, Pulteney Family Papers, University of Guelph Library, ref. XS1 MS A053.

The younger Malcolm began his naval career on the eve of his twelfth birthday. He set sail on Pasley’s ship, HMS Sibyl, from Plymouth on February 10, 1780, for a routine trip across the Atlantic to escort two Honourable East India Company (HEIC): A British joint-stock company founded in 1600 to trade in the Indian Ocean region. The company accounted for half the world’s trade from the 1750s to the early 1800s, including items such as cotton, silk, opium, and spices. It later expanded to control large parts of the Indian subcontinent by exercising military and administrative power. ships home.4Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 21. A “routine” trip was still a fraught one, when considering the pressure on the Royal Navy following the American Revolution. They were to escort the ships from the Cape of Good Hope, around Scotland, to a port in England. In 1781, Malcolm and Pasley joined HMS Jupiter under Commodore George Johnstone, William Pulteney’s brother.5Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 26. On April 16, Malcolm experienced his first action at sea: cannon fire exchanged with the French ship Annibal while anchored at the Cape Verde Islands. A year later, Pasley considered his nephew’s rank: “I am particularly anxious to get young Pulteney made a Lieutenant ere that [the war] ends.” At fourteen, Malcolm was ineligible to obtain the rank of lieutenant, a designation he desperately needed, as it came with an increase in pay.6Individuals had to be at least twenty to obtain the rank of lieutenant. As Pasley wrote, “His Father has not wherewithall to support half his Family. Misfortunes has bore hard upon him—fifteen children living is a very large Family.” Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley, Private Sea Journals, 1778–1782, ed. Rodney M. S. Pasley (London: Dent, 1931), 248. Pulteney lost two siblings to a fever (probably typhus) in 1779. Pasley’s solution was to transfer Malcolm to HMS Formidable to serve under Admiral Hugh Pigot, who promoted Malcolm to acting lieutenant in 1783.7Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, 1600–1815, ed. David Syrett and R. L. DiNardo (Aldershot: Navy Records Society, 1994), 296; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 31, 36, 40. “‘I’ll take care of him,’ says Admiral Pigot. It was enough; for he’s perfectly the Gentleman, and I know him to be a man of honor.” Pasley, Sea Journals, 254. Pigot could more easily promote within his own fleet.

Malcolm received several military promotions, including the rank of captain, before sitting for Smart’s 1809 portrait.8A. J. Scott, Recollections of the Life of the Revd A. J. Scott, D. D. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1842), 122; Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, January 14, 1810, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, ref. 6684/1; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 90, 99–100. Malcolm would command the Donegal for almost six years, the ship gaining the nickname “the Happy Donegal” because of Malcolm’s humane leadership. Malcolm’s most significant military action occurred during the battle of San Domingo on February 6, 1806; the British won this engagement with Napoleonic forces in the Caribbean, and Malcolm’s ship, HMS Donegal, captured the French ship Jupiter and rescued another, the Brave, which was quickly sinking. Malcolm saved all but two of the Brave’s crew members from drowning.9Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 106–7, 109. His heroic actions earned him a Captain’s Gold Medal,10Malcolm was also awarded an inscribed silver vase from Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund and a presentation in front of King George III. which is on display in his 1809 portrait. Smart skillfully recreates the medal’s scene of a winged figure crowning a standing Britannia.11For comparison, see Lewis Pingo, Naval Gold Medal (Captain’s) for San Domingo 1806, 1797, gold medal with a gold rim and watch glass, suspended from a gold loop and blue-edged white ribbon, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, MED2691.

The year 1809 was significant for Malcolm. While in London on December 16, 1808, he wrote a marriage proposal to Clementina Elphinstone (1775–1830), the sister of a former colleague:12Malcolm served alongside Colonel Charles Elphinstone in 1794, while post-captain of HMS Fox. The two were likely friends, and Malcolm may have written to the Elphinstone family to report on the search party for Charles, whose ship disappeared in a cyclone in 1807. Arthur Wellesley to John Malcolm, September 16, 1803, Wellington Papers, University of Southampton Hartley Library, ref. WP3/3/7 f.23; St. Margaret Parish Registers, Essex Records Office, Barking, ref. D/P 81/1/8; Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, n. d. [autumn 1810?], Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/1; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 51. “I have long derived much satisfaction from your friendship, and it has aroused in me the most sincere affection for you, and most truly will I rejoice if I find it mutual.”13Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, December 16, 1808, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/1. The rest of the letter reads, “To you who know me so well, I need not point out my situation in life. I will only say that with you I am confident my future life would be passed in comfort and happiness. I shall be most anxious for your answer, and most earnestly I pray that it may be propitious.” Malcolm and Clementina married a month later, on January 18, 1809.14Church of England Parish Records, London Metropolitan Archives, ref. P89/MRY1/181. Malcolm and Clementina had two sons together rather late in their lives, George Pulteney Malcolm (1814–1837) and William Elphinstone Malcolm (1817–1907). Clementina suffered at least two miscarriages; she describes her near-death experience while in labor in a heart-wrenching letter to Malcolm, see Clementina Malcolm to Pulteney Malcolm, February 17, 1814, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/11. The couple honeymooned in Portsmouth for two weeks and returned to London in February, which aligns with the inscribed date on the back of the miniature’s case, solidifying the theory that it is a marriage portrait.15Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 124. While two portrait miniatures of Clementina exist, none are known to be by John Smart. A portrait of “Lady Clementina Malcolm” by an unknown artist sold as the lot directly before the Nelson-Atkins portrait of Pulteney Malcolm; see Christie’s Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu and Miniatures (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, July 18, 1949), 8, lot 54.

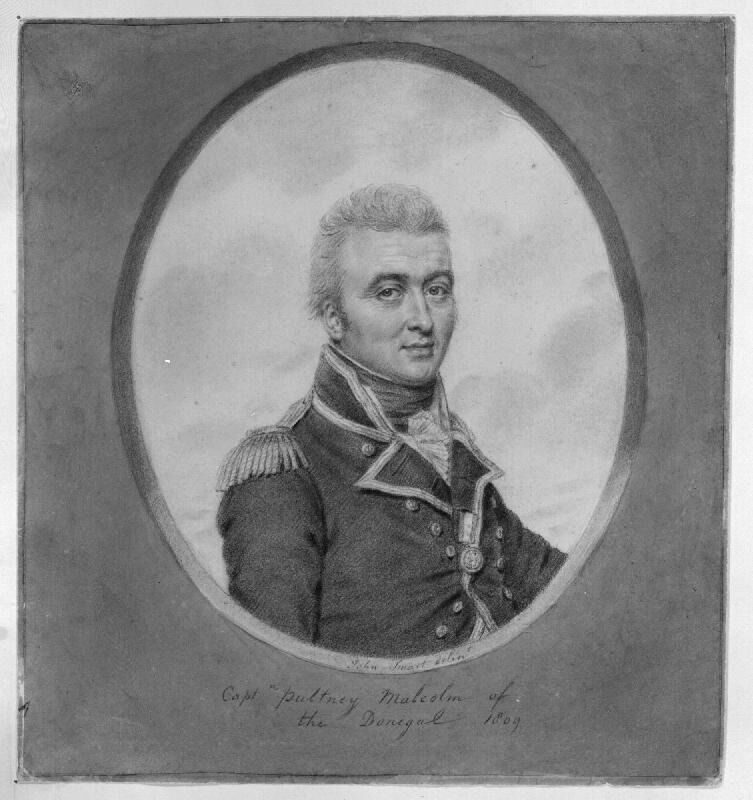

The miniaturist George Engleheart (1750–1829) also completed portraits of Malcolm in 1806 and 1807, as well as six of Malcolm’s relatives (Fig. 1).16George Engleheart, Sir Pulteney Malcolm, 1806, watercolor on ivory, 3 15/16 in. (10 cm) high, sold at Bonhams, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” London, April 8, 2010, lot 103. The lot description for this portrait notes that Engleheart’s 1807 portrait sold at Sotheby’s, “Silhouettes and Important Portrait Miniatures,” London, October 19, 1981, lot 170. These portraits were likely completed while Malcolm was in London receiving honors for his victory in the Battle of San Domingo. Engleheart also painted Malcolm’s brother, Charles Malcolm, in 1806; his wife’s father, William Fullerton Elphinstone, and her uncles Col. Charles Elphinstone in 1795; Lieutenant Colonel James Drummond Elphinstone in 1798; Major General George Elphinstone, or Lord Keith, in 1808; and John Fullerton Elphinstone in circa 1795. It unclear why Malcom would suddenly commission a portrait by Smart after sitting for Engleheart just two years earlier. It is possible that Smart approached Malcolm about including him in a print of naval commanders, following his accomplishments at San Domingo, which would also explain the existence of his completed drawing of Malcolm (Fig. 2).17It depicts Malcolm in the same posture and attire as the Nelson-Atkins portrait, but a trompe l’oeil composition and sky background indicates that Smart intended it as a finished, rather than preparatory, drawing.

At the age of forty-one and newly married, Malcolm is depicted here with nearly fully gray hair. He is the ideal gentleman, a courteous naval officer that the military branch desperately needed represented.18At this time, naval officers were generally viewed as rough and crude; see Amy Miller, Dressed to Kill: British Naval Uniform, Masculinity and Contemporary Fashions, 1748–1857 (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 2007), 7. Smart captures the respectful demeanor of this naval officer, whom many considered one of the fairest and most valued in British military history.19While his legacy is often overshadowed by that of his mentor and friend, Admiral Horatio Nelson, Malcolm spent more than thirty years of his life at sea and devoted his retirement to serving his country in administrative roles. According to a Royal Navy form Malcolm completed in 1816, he spent thirty-three years and four months in active service; see Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 198.

After retiring from active duty in 1815, Malcolm served as commander-in-chief on Saint Helena island, guarding the exiled Napoleon Bonaparte.20John Marshall, “Malcolm, Pulteney,” Royal Naval Biography (London: Longman, 1823), 1:597; Pulteney Malcolm to Nancy Malcolm, December 27, 1815, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/6. Malcolm was appointed vice-admiral on July 19, 1821, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet from 1828–1831 and 1833–1834, and Admiral of the Blue in 1837, before dying one year later. See Clementina Malcolm, A Diary of St. Helena: The Journal of Lady Malcolm, ed. Sir Arthur Wilson (New York: Harper, 1829). Napoleon’s description of Malcolm befits the likeness captured by Smart: “His countenance bespeaks his heart, and I am sure he is a good man; I never yet beheld a man of whom I so immediately formed a good opinion as of that fine, soldier-like old man: there is the face of an English-man; a countenance pleasing, open, intelligent, frank, sincere.”21Antoine-Vincent Arnault, Memoirs of the Public and Private Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, trans. W. Hamilton Reid (London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1826), 867; Sir Walter Scott, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte (Germany: Outlook, 2020), 5:309.

Notes

-

Paul Martinovich, The Sea is My Element: The Eventful Life of Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, 1768–1838 (Warwick: Helion, 2021), 18.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 18. George declared bankruptcy in 1780 because his side business of importing wine in the Canary Islands failed, which likely forced him to find professions for his four oldest sons.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 19. Captain Pasley arranged for Malcolm to live at his sister’s house in Portsmouth, while also paying for his nephew’s additional schooling. A 1780 letter from George to William Pulteney documents these major life events: “My third Son who has the Honour to be your Name has been at an Academy for about a Year in the Neighborhood of South Hampton where Mr. Briggs [Pasley’s sister’s husband] now lives. He was there at the Expense of Captain Pasley. I have got from all his friends very flattering Accounts of his Progress. He is now going to Sea with his Uncle.” George Malcom to William Pulteney, February 11, 1780, Pulteney Family Papers, University of Guelph Library, ref. XS1 MS A053.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 21. A “routine” trip was still a fraught one, when considering the pressure on the Royal Navy following the American Revolution. They were to escort the ships from the Cape of Good Hope, around Scotland, to a port in England.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 26. On April 16, Malcolm experienced his first action at sea: cannon fire exchanged with the French ship Annibal while anchored at the Cape Verde Islands.

-

Individuals had to be at least twenty to obtain the rank of lieutenant. As Pasley wrote, “His Father has not wherewithall to support half his Family. Misfortunes has bore hard upon him—fifteen children living is a very large Family.” Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley, Private Sea Journals, 1778–1782, ed. Rodney M. S. Pasley (London: Dent, 1931), 248. Pulteney lost two siblings to a fever (probably typhus) in 1779.

-

Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, 1600–1815, ed. David Syrett and R. L. DiNardo (Aldershot: Navy Records Society, 1994), 296; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 31, 36, 40. “‘I’ll take care of him,’ says Admiral Pigot. It was enough; for he’s perfectly the Gentleman, and I know him to be a man of honor.” Pasley, Sea Journals, 254. Pigot could more easily promote within his own fleet.

-

A. J. Scott, Recollections of the Life of the Revd A. J. Scott, D. D. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1842), 122; Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, January 14, 1810, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, ref. 6684/1; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 90, 99–100. Malcolm would command the Donegal for almost six years, the ship gaining the nickname “the Happy Donegal” because of Malcolm’s humane leadership.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 106–7, 109.

-

Malcolm was also awarded an inscribed silver vase from Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund and a presentation in front of King George III.

-

For comparison, see Lewis Pingo, Naval Gold Medal (Captain’s) for San Domingo 1806, 1797, gold medal with a gold rim and watch glass, suspended from a gold loop and blue-edged white ribbon, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, MED2691.

-

Malcolm served alongside Colonel Charles Elphinstone in 1794, while post-captain of HMS Fox. The two were likely friends, and Malcolm may have written to the Elphinstone family to report on the search party for Charles, whose ship disappeared in a cyclone in 1807. Arthur Wellesley to John Malcolm, September 16, 1803, Wellington Papers, University of Southampton Hartley Library, ref. WP3/3/7 f.23; St. Margaret Parish Registers, Essex Records Office, Barking, ref. D/P 81/1/8; Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, n. d. [autumn 1810?], Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/1; Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 51.

-

Pulteney Malcolm to Clementina Malcolm, December 16, 1808, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/1. The rest of the letter reads, “To you who know me so well, I need not point out my situation in life. I will only say that with you I am confident my future life would be passed in comfort and happiness. I shall be most anxious for your answer, and most earnestly I pray that it may be propitious.”

-

Church of England Parish Records, London Metropolitan Archives, ref. P89/MRY1/181. Malcolm and Clementina had two sons together rather late in their lives, George Pulteney Malcolm (1814–1837) and William Elphinstone Malcolm (1817–1907). Clementina suffered at least two miscarriages; she describes her near-death experience while in labor in a heart-wrenching letter to Malcolm; see Clementina Malcolm to Pulteney Malcolm, February 17, 1814, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/11.

-

Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 124. While two portrait miniatures of Clementina exist, none are known to be by John Smart. A portrait of “Lady Clementina Malcolm” by an unknown artist sold as the lot directly before the Nelson-Atkins portrait of Pulteney Malcolm; see Christie’s Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu and Miniatures (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, July 18, 1949), 8, lot 54.

-

George Engleheart, Sir Pulteney Malcolm, 1806, watercolor on ivory, 3 15/16 in. (10 cm) high, sold at Bonhams, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” London, April 8, 2010, lot 103. The lot description for this portrait notes that Engleheart’s 1807 portrait sold at Sotheby’s, “Silhouettes and Important Portrait Miniatures,” London, October 19, 1981, lot 170. These portraits were likely completed while Malcolm was in London receiving honors for his victory in the Battle of San Domingo. Engleheart also painted Malcolm’s brother, Charles Malcolm, in 1806; his wife’s father, William Fullerton Elphinstone, and her uncles Col. Charles Elphinstone in 1795 and Lieutenant Colonel James Drummond Elphinstone in 1798; Major General George Elphinstone, or Lord Keith, in 1808; and John Fullerton Elphinstone in circa 1795.

-

It depicts Malcolm in the same posture and attire as the Nelson-Atkins portrait, but a trompe l’oeil composition and sky background indicate that Smart intended it as a finished, rather than preparatory, drawing.

-

At this time, naval officers were generally viewed as rough and crude; see Amy Miller, Dressed to Kill: British Naval Uniform, Masculinity and Contemporary Fashions, 1748–1857 (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 2007), 7.

-

While his legacy is often overshadowed by that of his mentor and friend, Admiral Horatio Nelson, Malcolm spent more than thirty years of his life at sea and devoted his retirement to serving his country in administrative roles. According to a Royal Navy form Malcolm completed in 1816, he spent thirty-three years and four months in active service; see Martinovich, The Sea is My Element, 198.

-

John Marshall, “Malcolm, Pulteney,” Royal Naval Biography (London: Longman, 1823), 1:597; Pulteney Malcolm to Nancy Malcolm, December 27, 1815, Malcolm of Burnfoot Papers, ref. 6684/6. Malcolm was appointed vice-admiral on July 19, 1821, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet from 1828–1831 and 1833–1834, and Admiral of the Blue in 1837, before dying one year later. See Clementina Malcolm, A Diary of St. Helena: The Journal of Lady Malcolm, ed. Sir Arthur Wilson (New York: Harper, 1829).

-

Antoine-Vincent Arnault, Memoirs of the Public and Private Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, trans. W. Hamilton Reid (London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1826), 867; Sir Walter Scott, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte (Germany: Outlook, 2020), 5:309.

Provenance

Commissioned by Pulteney (1768–1838) and Clementina (1775–1830) Malcolm, Burnfoot, Westerkirk, Scotland, around February 7, 1809 [1];

To their son, William Elphinstone Malcolm (1817–1907), Burnfoot, Westerkirk, Scotland, by 1838 [2];

By descent to his daughter, Mary Palmer Douglas Malcolm (1859–1949), Cavers, Scotland, by 1907–1949 [3];

Purchased from her posthumous sale, Objects of Art and Vertu and Miniatures, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, July 18, 1949, lot 55, as Captain Sir Pultney [sic] Malcolm, by “Baker” (probably Hans Backer), London, 1949 [4];

Probably purchased from Backer by Sir Bruce Stirling Ingram (1877–1963), London, 1949–1963 [5];

Purchased from his posthumous sale, Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu, Sotheby’s, London, July 20, 1964, lot 51, as Captain Pultney Malcolm, by Charles Woollett and Son, London, 1964 [6];

Probably purchased from Woollett by Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965 [7];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] In the Christie’s July 18, 1949, sale catalogue, “Different Properties” sold lots 47–66. Lots 52–55 depict members of the Elphinstone and Malcolm family, which suggests that the same individual, probably a relative, sold all four lots. Specifically, they depict Pulteney and Clementina; her father William Fullerton Elphinstone (1740–1834); and their sons George (1814–1837) and William (Hon. William Elphinstone, 1817–1907) by Andrew Robertson (in a leather case); Pulteney Malcolm, a cameo by Samuel Andrew; and, in the same lot, a silhouette of Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh C. Christian (in a leather case); George Pulteney and William Elphinstone Malcolm as infants (in a leather case), and, in the same lot, Lady Clementina Malcolm (in a leather case); and Pulteney Malcolm by John Smart (in a leather case). Pulteney had a sister named Helen Elphinstone Malcolm (1771–1858). Her name suggests a further connection to Clementina Elphinstone’s family, but there are not enough details to make a direct link.

[2] 1838 was the year William’s father and the sitter, Pulteney, died.

[3] Pulteney Malcolm’s only grandchild, Mary Palmer Douglas Malcolm, died on May 20, 1949, two months before the family’s portraits were sold. Pulteney Malcolm’s son George died young, so William was the only one to marry. He married Mary Douglas in 1857 and they had one child: Mary, who later married Captain Edward Palmer in 1879. When she died, her estate’s death duties were financially fatal. This could explain why the family sold the portraits. See Hawick Archeological Society, Transactions of the Hawick Archaeological Society (Hawick: Scott and Paterson, 1949), 53.

[4] It was described in the sales catalogue as “Portrait of Captain Sir Pultney [sic] Malcolm by John Smart, signed with initials and dated 1809, three-quarter face to the left, in gold-faced naval coat and black stock—oval, 3 3/4 in. high, leather case.” Although Mary Palmer Douglas Malcolm’s identity as the seller is not definitive, there is a high degree of confidence this was her sale, based on the other family portraits in the surrounding lots, the date of her death two months prior to the auction, and her financial debts at the time of her death.

According to Art Prices Current 25 (1947–1949), “Baker” bought lot 55 for £50 8s, but as was the case with this published record of annual sales, the name is probably misspelled and should be “Backer.” It most likely refers to Hans Backer, who was a popular miniature dealer and sometimes bid for the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This name comes up in Starr correspondence (see letter, October 11, 1955, University of Missouri-Kansas City archives, box 22, folder 9).

[5] Ingram was actively collecting naval works of art in 1949, including the John Smart portrait in pencil, Captain Pulteney Malcolm of the Donegal, 1809, pencil and wash, 5 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (14.9 x 14 cm), The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA. Sir Bruce Ingram Collection, 63.52.235.

[6] It was described in the sales catalogue as “A Fine Miniature of Captain Pultney [sic] Malcolm by John Smart, signed and dated 1809, three-quarters sinister, gaze directed at spectator, his grey hair cropped short and wearing a blue, gold-braided naval uniform, over a white shirt and black cravat, large oval 3 3/4 in., fitted case. Daphne Foskett, John Smart, illustrated a pen and wash miniature of Captain Malcolm, afterwards Admiral Sir Pultney [sic] Malcolm, signed in full by Smart and also dated 1809; it too was formerly in the collection of the late Sir Bruce Ingram.” The catalogue for this sale is located at University of Missouri-Kansas City, Miller Nichols Library. Lot 51 is reproduced on the frontispiece. According to an attached price list, “Woollett” purchased the miniature for £240 / $672.00.

[7] There is a 1964 letter in the Nelson-Atkins Registration file addressed to Woollett and Son from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. It describes the military career of Sir Pulteney Malcom. Charles Woollett and Son, London, was a respectable fine arts dealer, who frequently purchased portrait miniatures in the mid-1900s.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Captain Pultney [sic] of the Malcolm.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no. 142, as Captain Pultney [sic] of the Malcolm.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Pulteney Malcolm, Captain of the Donegal.

References

Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu and Miniatures (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, July 18, 1949), lot 55, as Captain Sir Pultney [sic] Malcolm.

Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu (London: Sotheby’s, July 20, 1964), lot 51, (repro. frontispiece), as Captain Pultney [sic] Malcolm.

Antiques 90 (July–December 1966): 357, fig. 15, as Captain (later Vice-Admiral) Sir Pulteney Malcolm.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 142, p. 50, (repro.), as Captain Pultney [sic] of the Malcolm.

Paul Martinovich, The Sea Is My Element: The Eventful Life of Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, 1766–1838 (Warwick: Helion Limited, 2021), plate IX, no. 10, as Malcolm.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.