Citation

Chicago:

Maggie Keenan, “John Smart, Portrait of John Wells, Rear-Admiral of the White, 1808,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1634.

MLA:

Keenan, Maggie. “John Smart, Portrait of John Wells, Rear-Admiral of the White, 1808,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1634.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

John Wells (1763–1841) was believed to be the

illegitimate child of Royal Navy Admiral Augustus

Keppel (1725–1786), a rumor supported by his mother’s

hope for his success in the army or navy.1William Smith, Old Yorkshire (London:

Longmans, Green, 1890), 149. John Wells’s mother,

Sarah Wells, was Keppel’s mistress, so his father

may have been Keppel or his mother’s previous

partner, “a low fellow, who used her very ill,”

according to

Town and Country Magazine (September

1771): 459. This account continues: “[She] hopes

that he will one day make a very capital figure in

the army or navy.” For a portrait of Wells as a

child, see George Romney,

Portrait of John Wells When a Boy, ca.

1770, oil on canvas, in a painted oval, dimensions

unknown, listed for sale at “Important British

Paintings,” Sotheby’s, London, November 22, 2007,

lot 51,

https://www.sothebys.com

Wells saw the most military action between 1780 and 1800.3In 1783, while Wells was serving as commander of the HMS Raven, the ship was taken hostage by two French frigates. Wells endured a short period of captivity before being released and promoted to captain. Isaac Schomberg, Naval Chronology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 5:45. While serving as captain of the Lancaster in 1797, he was caught in the Nore Mutiny, a large-scale sailor uprising.4Jean-Marc Hill, “The Many Faces of Richard Parker: President of the ‘Floating Republic,’” Royal Museums Greenwich (blog), June 7, 2019, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/richard-parker-nore-mutiny-rebellion-retribution-royal-navy. Two river workers helped Wells escape the revolt by climbing through a gunport. Wells would eventually return to the ship to accept the mutineers’ surrender in return for their full pardon and the execution of their ringleader.5Jeffery Duane Glasco, “We Are a Neglected Set,” in “Masculinity, Mutiny, and Revolution in the Royal Navy of 1797” (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2001), 264–65; Hill, “The Many Faces of Richard Parker.” It has been debated whether the “leader” Richard Parker was in charge of the mutiny or simply a scapegoat. The Lancaster rejoined the British fleet a few months later, fighting Dutch forces at the Battle of Camperdown (1797).

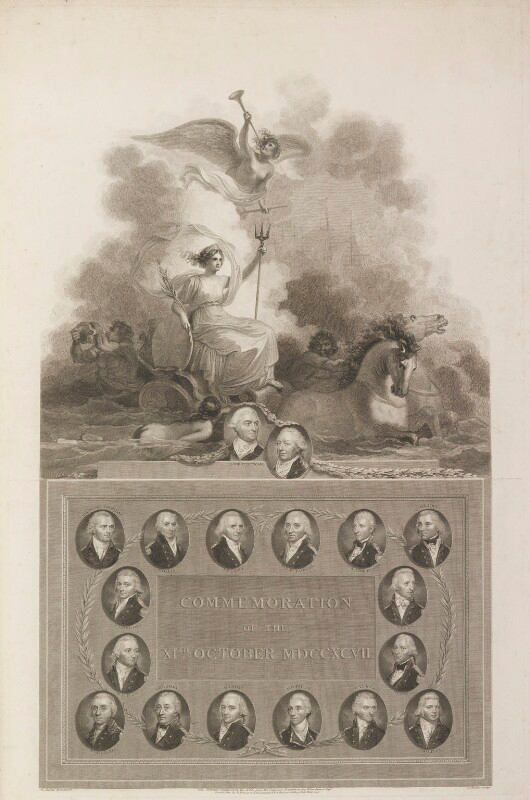

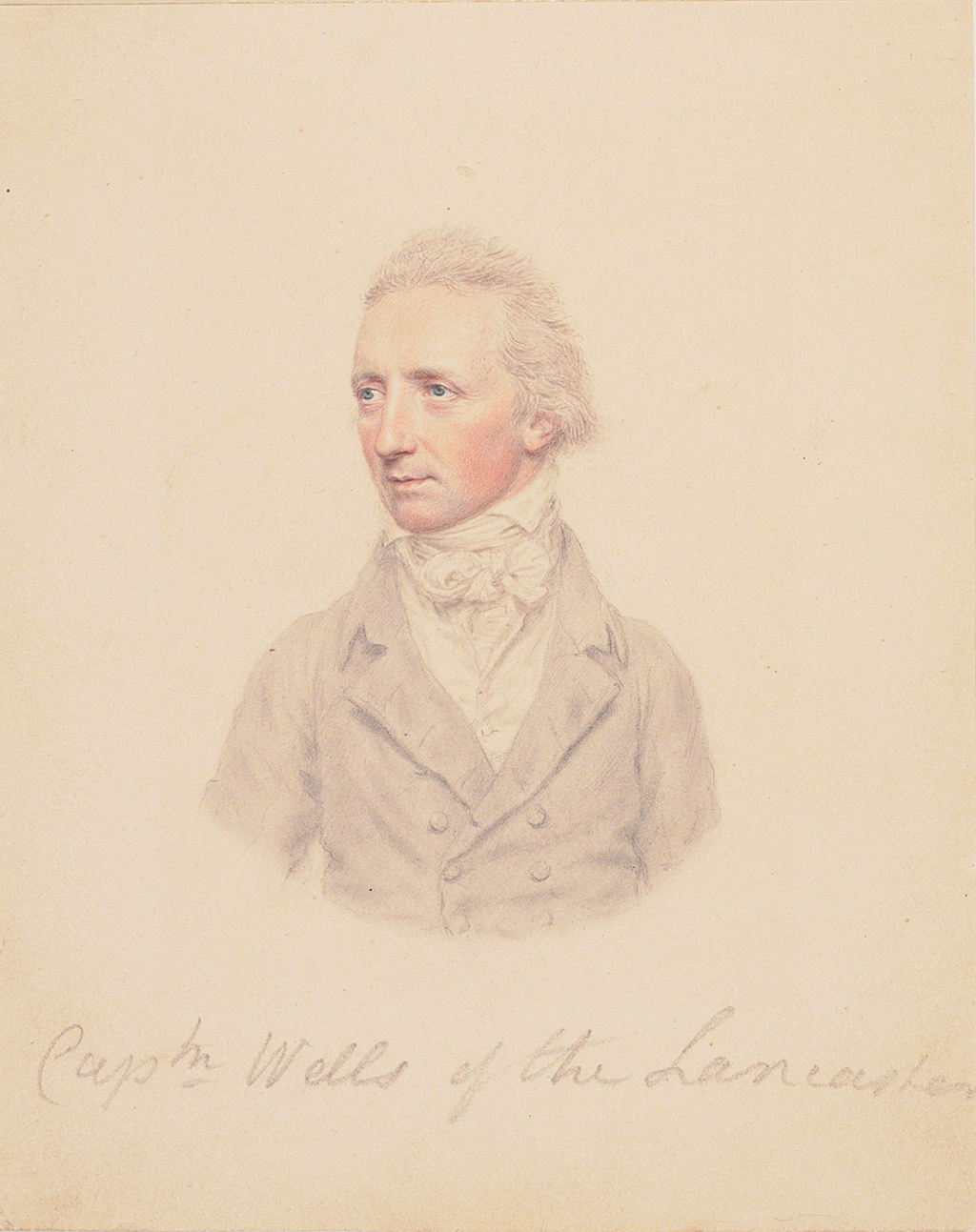

Wells received a Naval Gold Medal6Lewis Pingo, Naval Gold Medal (Captain’s) for The Battle of Camperdown, 1797, 1 1/3 in. (3.3 cm) diam., National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-40615. for his actions in battle and was featured in an engraving by Robert Smirke (1753–1845) commemorating the event (Fig. 1).7The engraving was done by Robert Smirke and was later published by Robert Bowyer. The National Portrait Gallery erroneously identifies Captain John Wells as Captain Josiah Robert Wells. The engraving of Wells was based on a preparatory drawing by John Smart, who was close friends with Smirke (Fig. 2).8The Nelson-Atkins portrait was formerly called Portrait of Vice Admiral Thomas Wells; however, the preparatory drawing’s inscription, likely in Smart’s hand, “Captn Wells of the Lancaster,” confirms that is John Wells, Captain of the Lancaster. The only difference between the drawing and engraving is his clothing: Smart depicts Wells in civilian clothing, whereas Smirke shows him in a naval uniform. The drawing is, however, nearly identical to the watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. in the Nelson-Atkins collection, prompting speculation as to why Smart painted it nearly ten years after his preparatory drawing.9The drawing includes more of Wells’s coat and buttons, but otherwise they closely mirror each other. Both versions include detailed facial features, like the blue veins that wander up Wells’s left temple. The Nelson-Atkins miniature cannot be justified as a marriage portrait, since Wells married much later, in 1815. Wells married Jane Dealtry (1769–1844) on April 22, 1815, in Clayton, Sussex. See England & Wales Marriages, 1538–1988: 1815, film no. 1068522, digitized on Ancestrylibrary.com.

The Nelson-Atkins miniature probably documents Wells’s appointment to Rear-Admiral of the White: A senior rank of the Royal Navy. The order of precedence, from lowest to highest, went: Rear-Admiral of the Blue, Rear-Admiral of the White, Rear-Admiral of the Red, Vice-Admiral of the Blue, Vice-Admiral of the White, Vice-Admiral of the Red, Admiral of the Blue, Admiral of the White, Admiral of the Red, and then Admiral of the Fleet. on April 28, 1808.10David Syrett and R. L. DiNardo, The Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, 1660–1815 (Aldershot: Scholar Press, 1994), 463. Smart depicts Wells in a brown coat with an intricately tied cravat: A cravat, the precursor to the modern necktie and bowtie, is a rectangular strip of fabric tied around the neck in a variety of ornamental arrangements. Depending on social class and budget, cravats could be made in a variety of materials, from muslin or linen to silk or imported lace. It was originally called a “Croat” after the Croatian military unit whose neck scarves first caused a stir when they visited the French court in the 1660s., against a gray background. The absence of a uniform is striking, especially for a man who spent most of his life climbing the naval ranks.11Another example of this is Smart’s portrait of Keith MacAlister; the Nelson-Atkins portrait on ivory depicts him in his military uniform, while a preparatory version at the Cleveland Museum of Art shows him in civilian clothing. See Portrait of Keith MacAlister, Colonel of the 5th Madras Native Cavalry (1810), and Portrait of General Keith MacAlister, ca. 1800–1810, watercolor and graphite, heightened with traces of white gouache, on paper, image: 5 3/16 x 4 1/2 in. (13.2 x 11.4 cm); sheet: 6 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (17.4 x 14 cm), Cleveland Museum of Art, 1997.77, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1997.77. Wells may have preferred his civilian appearance, or possibly the more time- and cost-efficient option of copying an earlier drawing, rather than sitting for a new portrait.12The majority of Keppel’s portraits depict him in his Royal Navy uniform. There is, however, one exception: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Admiral Viscount Keppel, 1780, oil on canvas, 49 x 39 in. (124.5 x 99.1 cm), Tate, London, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/reynolds-admiral-viscount-keppel-n00886. Keppel was close friends with Reynolds (1723–1792), but other portraits by Reynolds of Keppel display him in uniform.

Wells was eventually appointed Admiral in 1821, the

highest naval rank obtainable. Additionally, he was

knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the

Bath and then advanced to Knight Grand Cross in

1834.13Syrett and DiNardo,

Commissioned Sea Officers, 463.

Wells died on November 19, 1841, at the age of

seventy-eight.14Urban, “Obituary,” 554. Wells and his wife did

not have any children. His wife outlived him, so

when she died, their wealth and estates went to

his wife’s sister and cousin. See provenance for

Romney,

Portrait of John Wells When a Boy (see n.

1),

https://www.sothebys.com

Notes

-

William Smith, Old Yorkshire (London: Longmans, Green, 1890), 149. John Wells’s mother, Sarah Wells, was Keppel’s mistress, so his father may have been Keppel or his mother’s previous partner, “a low fellow, who used her very ill,” according to Town and Country Magazine (September 1771): 459. This account continues: “[She] hopes that he will one day make a very capital figure in the army or navy.” For a portrait of Wells as a child, see George Romney, Portrait of John Wells When a Boy, ca. 1770, oil on canvas, in a painted oval, dimensions unknown, listed for sale at “Important British Paintings,” Sotheby’s, London, November 22, 2007, lot 51, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/important-british-paintings-l07123/lot.51.html.

-

Sylvanus Urban, “Obituary,” Gentleman’s Magazine 172 (January–June 1842): 554. Wells likely served as a midshipman prior to his appointment of lieutenant. Following the battle, Keppel was court-martialed twice due to avoiding engaging the enemy, but the disapproval was much fueled by political differences in Parliament. Keppel was eventually cleared of misconduct in action.

-

In 1783, while Wells was serving as commander of the HMS Raven, the ship was taken hostage by two French frigates. Wells endured a short period of captivity before being released and promoted to captain. Isaac Schomberg, Naval Chronology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 5:45.

-

Jean-Marc Hill, “The Many Faces of Richard Parker: President of the ‘Floating Republic,’” Royal Museums Greenwich (blog), June 7, 2019, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/richard-parker-nore-mutiny-rebellion-retribution-royal-navy.

-

Jeffery Duane Glasco, “We Are a Neglected Set,” in “Masculinity, Mutiny, and Revolution in the Royal Navy of 1797” (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2001), 264–65; Hill, “The Many Faces of Richard Parker.” It has been debated whether the “leader” Richard Parker was in charge of the mutiny or simply a scapegoat.

-

Lewis Pingo, Naval Gold Medal (Captain’s) for The Battle of Camperdown, 1797, 1 1/3 in. (3.3 cm) diam., National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-40615.

-

The engraving was done by Robert Smirke and was later published by Robert Bowyer. The National Portrait Gallery erroneously identifies Captain John Wells as Captain Josiah Robert Wells.

-

The Nelson-Atkins portrait was formerly called Portrait of Vice Admiral Thomas Wells; however, the preparatory drawing’s inscription, likely in Smart’s hand, “Captn Wells of the Lancaster,” confirms that is John Wells, Captain of the Lancaster.

-

The drawing includes more of Wells’s coat and buttons, but otherwise they closely mirror each other. Both versions include detailed facial features, like the blue veins that wander up Wells’s left temple. The Nelson-Atkins miniature cannot be justified as a marriage portrait, since Wells married much later, in 1815. Wells married Jane Dealtry (1769–1844) on April 22, 1815, in Clayton, Sussex. See England & Wales Marriages, 1538–1988: 1815, film no. 1068522, digitized on Ancestrylibrary.com.

-

David Syrett and R. L. DiNardo, The Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, 1660–1815 (Aldershot: Scholar Press, 1994), 463.

-

Another example of this is Smart’s portrait of Keith MacAlister; the Nelson-Atkins portrait on ivory depicts him in his military uniform, while a preparatory version at the Cleveland Museum of Art shows him in civilian clothing. See Portrait of Keith MacAlister, Colonel of the 5th Madras Native Cavalry (1810), and Portrait of General Keith MacAlister, ca. 1800–1810, watercolor and graphite, heightened with traces of white gouache, on paper, image: 5 3/16 x 4 1/2 in. (13.2 x 11.4 cm); sheet: 6 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (17.4 x 14 cm), Cleveland Museum of Art, 1997.77, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1997.77.

-

The majority of Keppel’s portraits depict him in his Royal Navy uniform. There is, however, one exception: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Admiral Viscount Keppel, 1780, oil on canvas, 49 x 39 in. (124.5 x 99.1 cm), Tate, London, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/reynolds-admiral-viscount-keppel-n00886. Keppel was close friends with Reynolds (1723–1792), but other portraits by Reynolds of Keppel display him in uniform.

-

Syrett and DiNardo, Commissioned Sea Officers, 463.

-

Urban, “Obituary,” 554. Wells and his wife did not have any children. His wife outlived him, so when she died, their wealth and estates went to his wife’s sister and cousin. See provenance for Romney, Portrait of John Wells When a Boy (see n. 1), https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/important-british-paintings-l07123/lot.51.html.

-

Morning Post, November 25, 1841, 3. The three more senior admirals were Sir Charles Nugent, Sir J. H. Whitshed, and W. Wolsely. For the quote from Wells’s mother, see n. 1.

Provenance

Probably commissioned by John Wells (1763–1841), Bolnore, Cuckfield, Sussex, 1808–1841;

Probably inherited by his wife, Jane Wells (née Dealtry, 1769–1844), Bolnore, Cuckfield, Sussex, 1841–1844 [1];

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] According to the provenance compiled for George Romney, Portrait of John Wells When a Boy, ca. 1770, listed for sale at Important British Paintings, Sotheby’s, London, November 22, 2007, lot 51, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/important-british-paintings-l07123/lot.51.html, Jane Wells’s second cousin may have inherited her property. This cousin has not yet been identified.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Admiral Wells.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 141, as Admiral Wells.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of John Wells, Rear-Admiral of the White.

References

Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 75, as Admiral John Wells.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 141, p. 49, (repro.), as Admiral Wells.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.