Citation

Chicago:

Blythe Sobol, “John Smart, Portrait of John Buck of Halifax, 1802,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1620.

MLA:

Sobol, Blythe. “John Smart, Portrait of John Buck of Halifax, 1802,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1620.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

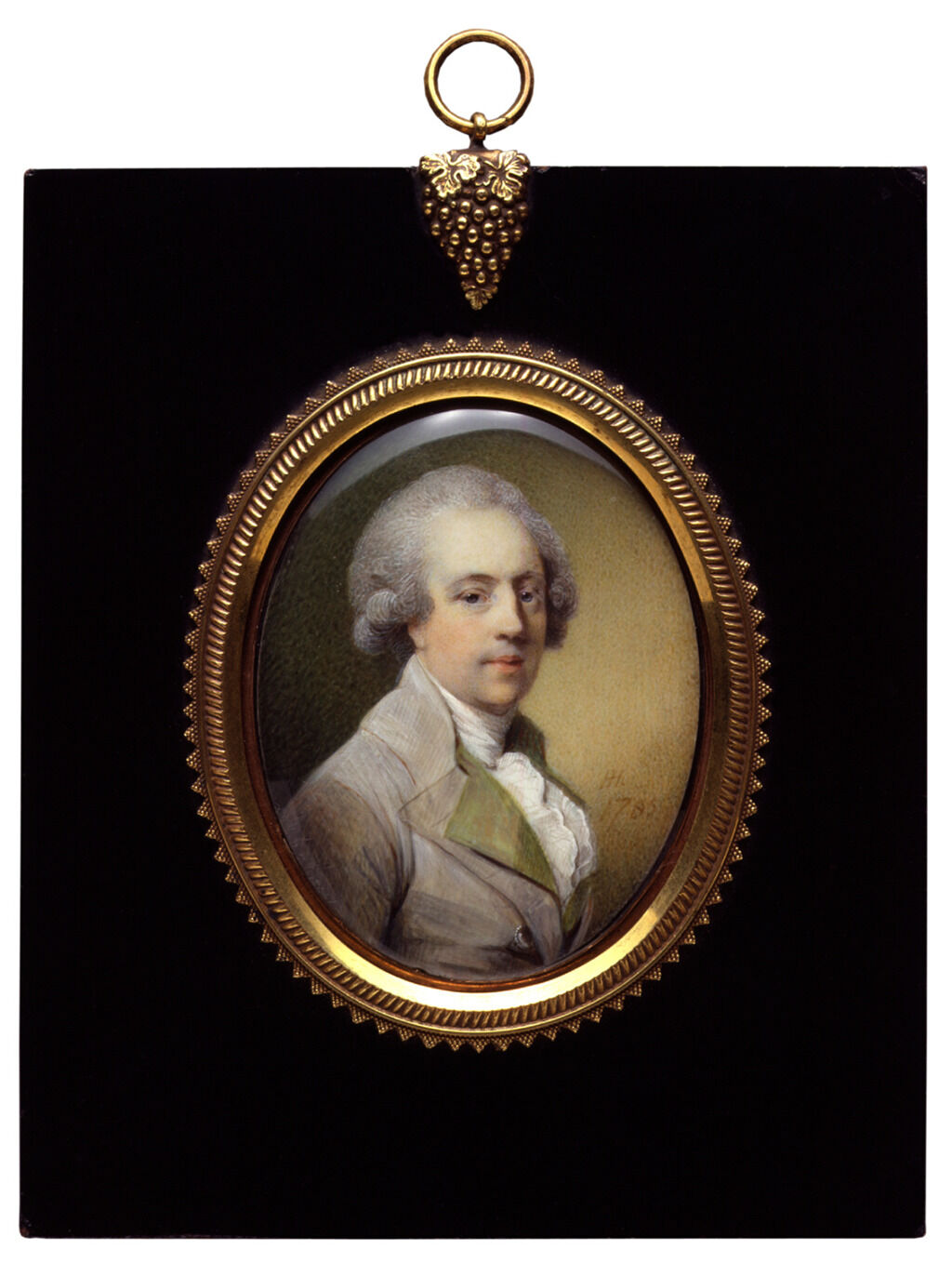

The man in this portrait was previously identified as Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744–1817), the Anglo-Irish politician, inventor, writer, and father of the celebrated novelist Maria Edgeworth, perhaps due to the letters “RE” monogrammed on the back of the case.1The initials could perhaps relate to a previous owner, or perhaps the case was switched with another including these initials, as was often done. However, a comparison of this example to numerous extant portraits of Richard Edgeworth reveals no resemblance. He had fleshy pursed lips, close-set eyes, and a distinctive high hairline, visible in all of his likenesses made over several decades (Fig. 1).2See also Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, ca. 1800, oil on canvas, 30 5/16 x 25 9/16 in. (77 x 65 cm), National Gallery of Ireland, Dulbin, http://onlinecollection.nationalgallery.ie/objects/2732. Note that another miniature by Smart, “traditionally identified as Richard Lovell Edgeworth,” does not resemble either the Nelson-Atkins sitter or Edgeworth: John Smart, A Gentleman Traditionally Identified as Richard Lovell Edgeworth, 1807, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm) high, sold at Bonham’s, London, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” November 19, 2014, lot 119, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/21452/lot/119/.

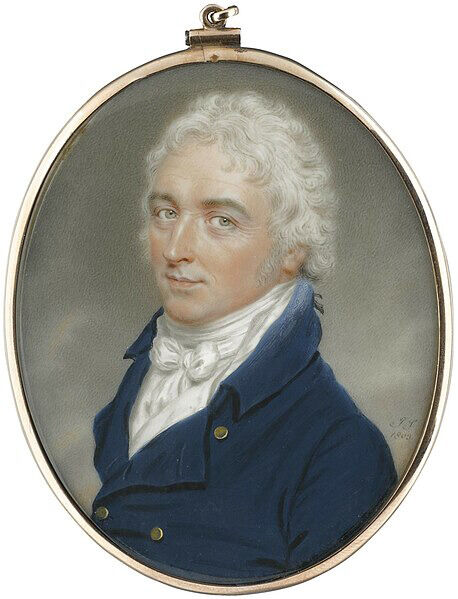

In fact, the sitter is almost certainly John Buck,

whose name is attached to a nearly identical miniature

by Smart painted three years later, in 1805 (Fig.

2).3John Smart,

Portrait of John Buck of Halifax, 1805,

watercolor on ivory, 3 1/16 x 2 1/2 in. (7.8 x 6.2

cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Important

Miniatures from a Private Collection,” April 16,

2008, lot 102,

https://www.sothebys.com

Buck otherwise appears typical among Smart’s patrons: prosperous but not overly fashionable, wearing a ubiquitous gold-buttoned blue coat and white cravat: A cravat, the precursor to the modern necktie and bowtie, is a rectangular strip of fabric tied around the neck in a variety of ornamental arrangements. Depending on social class and budget, cravats could be made in a variety of materials, from muslin or linen to silk or imported lace. It was originally called a “Croat” after the Croatian military unit whose neck scarves first caused a stir when they visited the French court in the 1660s. and vest. His white hair coloring was probably its natural color, rather than doused with powder, which had become deeply unfashionable, even in the more provincial areas of England, after the 1795 Duty on Hair Powder Act.5William Pitt introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act in Great Britain on May 5, 1795, as an Act of Parliament. Stephen Dowell, A History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Year 1885 (London: Longmans, Green, 1888), 3:255–59. Alas, like his attire, John Buck’s name is too commonplace to pinpoint a likely candidate with any certainty. At least three men named John Buck lived in West Yorkshire around the turn of the nineteenth century.6None of these men were recorded as living in Halifax, specifically. For example, a John Buck lived in Garsdale, which was once part of West Yorkshire (Garsdale is now part of Cumbria), in 1803, the year this miniature was painted. “John Buck,” West Yorkshire, England, Select Land Tax Records, 1704–1932, ref. QE13/13/13, digitized on ancestry.com. By that time, Halifax was becoming a thriving center of textile manufacturing, an industry in which this John Buck may have played a role.7Halifax was particularly known for its production of worsted and woolen fabrics. Paul Mantoux traces the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the textile industry through a case study of the weavers of West Yorkshire and Halifax in Paul Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century: An Outline of the Beginnings of the Modern Factory System in England (London: Methuen, 1964), 57–68.

Notes

-

The initials could perhaps relate to a previous owner, or perhaps the case was switched with another including these initials, as was often done.

-

See also Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, ca. 1800, oil on canvas, 30 5/16 x 25 9/16 in. (77 x 65 cm), National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, NGI.1350. Note that another miniature by Smart, “traditionally identified as Richard Lovell Edgeworth,” does not resemble either the Nelson-Atkins sitter or Edgeworth: John Smart, A Gentleman Traditionally Identified as Richard Lovell Edgeworth, 1807, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm) high, sold at Bonham’s, London, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” November 19, 2014, lot 119, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/21452/lot/119/.

-

John Smart, Portrait of John Buck of Halifax, 1805, watercolor on ivory, 3 1/16 x 2 1/2 in. (7.8 x 6.2 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Important Miniatures from a Private Collection,” April 16, 2008, lot 102, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2008/important-miniatures-from-a-private-collection-l08172/lot.102.html. The dimensions of the Nelson-Atkins and Sotheby’s miniatures are nearly identical; the difference of 1/16 of an inch in the width may be a result of human error. Likewise, the more muted coloring of the Sotheby’s portrait appears to be a difference in photographic reproduction, or perhaps fading pigments due to light exposure. The miniature’s features, even small areas of peachy orange in the sky background, such as just below the inscription on the lower right, closely match in both examples.

-

Sotheby’s listed the sitter’s identity as John Buck; see n. 3. No further information was provided, such as an interior backing card inscription, to substantiate this claim. However, given that Buck was not a major figure, it is unlikely the identity would have been randomly assigned, as occurs with more high-profile individuals.

-

William Pitt introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act in Great Britain on May 5, 1795, as an Act of Parliament. Stephen Dowell, A History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Year 1885 (London: Longmans, Green, 1888), 3:255–59.

-

None of these men were recorded as living in Halifax, specifically. For example, a John Buck lived in Garsdale, which was once part of West Yorkshire (Garsdale is now part of Cumbria), in 1803, the year this miniature was painted. “John Buck,“ West Yorkshire, England, Select Land Tax Records, 1704–1932, ref. QE13/13/13, digitized on ancestry.com.

-

Halifax was particularly known for its production of worsted and woolen fabrics. Paul Mantoux traces the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the textile industry through a case study of the weavers of West Yorkshire and Halifax in Paul Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century: An Outline of the Beginnings of the Modern Factory System in England (London: Methuen, 1964), 57–68.

Provenance

With Leo Schidlof (1886–1966), Vienna, by 1925 [1];

His sale, Versteigerung vom 5. bis 7. November 1925 in Leo Schidlof’s Kunstauktionshaus, Leo Schidlof’s Kunstauktionshaus, Vienna, November 5–7, 1925, lot 321 [2];

John W. (1905–2000) and Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] Leo Schidlof was an Austrian art dealer and art historian known to the Starrs. Schidlof’s book on portrait miniatures, The Miniature in Europe in the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries (Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1964) was published in several languages.

[2] The lot is described as “Bildnis eines Herrn in blauem Rock, In Goldmedaillon. Sign.: J.S. 1802. Elfenbein, oval, 7.8 : 6.2 cm” and reproduced on table 7 of the catalogue.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Called Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 135, as Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of John Buck of Halifax.

References

Versteigerung vom 5. bis 7. November 1925 in Leo Schidlof’s Kunstauktionshaus (Vienna: Leo Schidlof’s Kunstauktionshaus, November 5–7, 1925), 33, table 7, (repro.), as Bildnis eines Herrn in blauem Rock.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 135, p. 47, (repro.), as Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.