Citation

Chicago:

Maggie Keenan, “John Smart, Portrait of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1792,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1598.

MLA:

Keenan, Maggie. “John Smart, Portrait of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1792,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1598.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

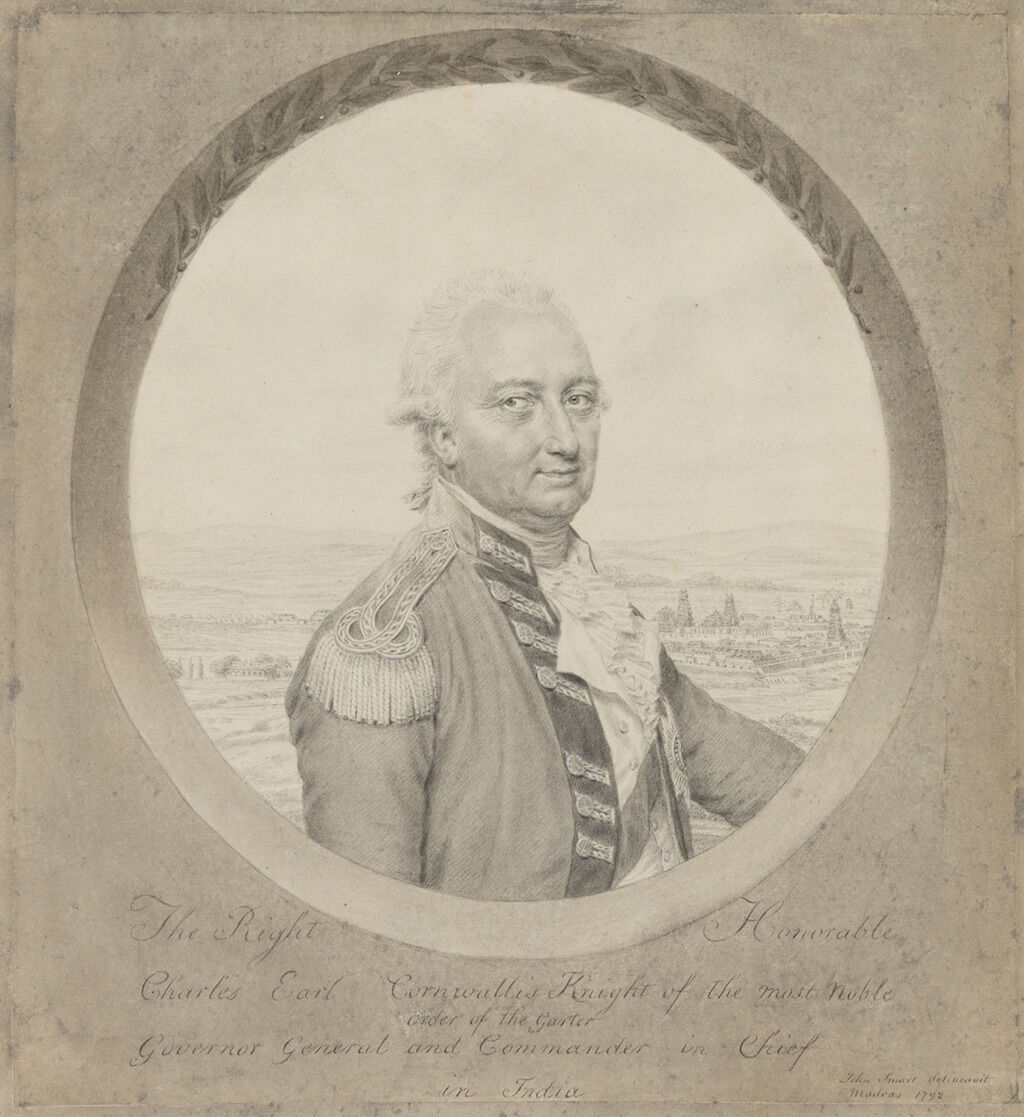

This portrait miniature of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis (1783–1805)1“Cornwallis, Charles, first Marquess Cornwallis,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 13:474. Cornwallis was born on December 31, 1738, to Charles, 5th Baron Cornwallis, later 1st Earl Cornwallis and Viscount Brome (1700–1762), and Elizabeth Townshend (1703–1785). Cornwallis married Jemima Tullekin (née Jones, 1747–1779), daughter of Regimental Colonel James Jones, in 1768, and they had two children: Charles, later Viscount Brome (1774–1823), and Mary (1769–1840). depicts a highly decorated British military and civil leader who, despite his lengthy list of accolades, shied away from public spectacle. John Smart recognized the potential market for Cornwallis’s image and viewed the general’s patronage as an opportunity to promote his own artistic ability. His interest in capitalizing on Cornwallis’s fame speaks more to the artist’s intentions than to Cornwallis’s own interests.2Cornwallis sat for other miniaturists, including Hugh Douglas Hamilton (Irish, ca. 1740–1808) in 1772, Diana Hill (English, ca. 1760–1844) in 1786, and William Grimaldi (English, 1751–1830) in 1810. See Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Portrait of General Charles Cornwallis, ca. 1770, pastel, 9 x 7 in. (22.9 x 17.8 cm), previously in the inventory of Philip Mould Ltd., London; Diana Dietz Hill, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1786, watercolor on ivory, 4 1/8 x 3 1/4 x 3/16 in. (10.5 x 8.3 x 5 cm), Mount Vernon Museum, H-4912, https://emuseum.mountvernon.org/objects/11032/charles-cornwallis-1st-marquess-cornwallis?ctx=31423f888d24e6becbc717c86e934ccf83be75c5&idx=0; William Grimaldi, Charles, 2nd Earl and 1st Marquess Cornwallis, ca. 1792–1798, 5 3/8 x 4 5/16 in. (13.6 x 10.9 cm), Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420856, https://www.rct.uk/collection/420856/charles-2nd-earl-and-1st-marquess-cornwallis-1738-1805. There is also a portrait of Cornwallis by Samuel Andrews (Irish, 1767–1807), but this is a copy after one of Smart’s portraits. See Attributed to Samuel Andrews, after John Smart, Portrait of Charles, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, ca. 1792, dimensions unknown, watercolor on ivory, Sotheby’s “Old Master Paintings” London sale, October 27, 2015, lot 603, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/old-master-paintings-l15035/lot.603.html.

Cornwallis’s lengthy military career saw many high and low points. Following his devastating surrender at the Battle of Yorktown (1781), which effectively won Americans their independence, Cornwallis, second in command of the British Army, retreated home to England, defeated.3For more on Cornwallis in the American Revolution, see Thomas Fleming, The Perils of Peace (New York: Dial Press, 1970), 16; Jerome Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2005), 294–97; David McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 146–48, 156–57, 191, 262. He gained another chance at leadership in 1786 with his appointment as governor-general and commander-in-chief in India, titles that gave him both military power and civil authority over the British-controlled regions of India.4“Cornwallis, Charles, first Marquess Cornwallis,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 13:474; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: The Imperial Years (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 17–18. Cornwallis held the titles until 1793. He was later appointed Commander-in-Chief and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1798, an office he held until 1801, and one he did not particularly enjoy: “The life of a Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland comes up to my idea of perfect misery, but if I can accomplish the great object of consolidating the British Empire, I shall be sufficiently repaid,” according to Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis, ed. Charles Ross (London: John Murray, 1859), 2:358. He was reappointed Lord Lieutenant of India in 1805 but died soon after his arrival and is buried on the banks of the Ganges at Ghazipur.

This new posting introduced Cornwallis to Smart, who had moved to India a year earlier and was looking to profit from portraits of celebrated military leaders.5Smart worked in India from 1785 to 1795. In 1792, Cornwallis invaded the Mysorean capital at Seringapatam under its ruler, Tipu Sultan (1751–1799), seizing the conquered territory and subsequently signing a peace treaty with the Nawab Muhammad Ali (1717–1795).6James Talboys Wheeler, India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal and Burma (New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1899), 2:489. Despite his success in Seringapatam, Cornwallis’s image was still represented satirically in the press. In James Gillray’s The Coming-On of the Monsoons; —or—The Retreat from Seringapatam, 1791, hand-colored etching, 8 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (22.3 x 27.5 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D13008, Cornwallis is depicted fleeing the battle of Seringapatam on donkey, with the inscription “What’s the matter, Falstaff?”, a reference to William Shakespeare’s overweight and comedic character. In response to his victory, Cornwallis was created 1st Marquess Cornwallis, likely occasioning the commission of this portrait.7The Nelson-Atkins portrait was likely in the collection of Jeffery Ludlam Barton Whitehead (1831–1915), who first lent the miniature to the Royal Academy’s Winter Exhibition in 1879; see Royal Academy of Arts, Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School, Including Oil Paintings, Miniatures, and Drawings: Winter Exhibition (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1879), 10:65, no. 23, as Charles, 1st Marquis of Cornwallis. The same miniature was likely sold at Christie’s “Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu, Watches, Miniatures, and Coins,” London, November 13, 1950, lot 89, as Portrait of Charles 1st Marquis Cornwallis, and shortly after acquired by the Starrs. Cornwallis also received the premier English order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter, in 1786 from King George III.

While these advancements in military and aristocratic rank reinforced Cornwallis’s significance as a sitter, the physical ornamentation of these distinctions made Cornwallis uncomfortable. Writing to his son, he outlines his reticence: “Soon after I left England I was elected Knight of the Garter, and [sic] very likely laughed at me for wishing to wear a blue riband over my fat belly.”8Correspondence of Charles, 1:247. The letter was sent from Calcutta and dated December 28, 1786. See George Charles Williamson, The History of Portrait Miniatures (London: George Bell and Sons, 1904), 2:2, plate 70. His embarrassment about the blue ribbon may explain why he is depicted wearing it in William Grimaldi’s portrait of Cornwallis, and not as prominently in Smart’s. See Grimaldi, Charles, 2nd Earl and 1st Marquess Cornwallis, the Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420856. As an artist who reveled in minute details, Smart depicted Cornwallis in his lieutenant-general uniform with his eight-pointed silver Star of the Garter and blue sash in nine portraits over an eight-year period—the second most he painted of a single sitter (Fig. 1).9John Smart, Portrait Miniature of Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1786, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm) high, previously in the inventory of Philip Mould Ltd., London; John Smart, Portrait of Charles Marquis Cornwallis, 1787, sold at Christie’s “Catalogue of Old Sèvres Porcelain, Old English Miniatures, Old French Gold and Enamel Boxes, Watches, and Objects of Vertu, Bronzes and other Objects of Art,” London, May 15, 1903, lot 28; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1791, watercolor on ivory, 2 3/4 in. (7 cm) high, sold at Christie’s “Centuries of Style: Silver, European Ceramics, Portrait Miniatures and Gold Boxes,” London, November 27, 2012, lot 393; John Smart, Charles, 1st Marquis Cornwallis, 1792, watercolor on ivory, 2 3/8 in. (6 cm) high, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 3922; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1792, pencil and gray wash, 7 1/4 x 6 5/8 in. (18.4 x 16.8 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 4316; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1793, watercolor on ivory, unknown dimensions, previously in the inventory of Elle Shushan; John Smart, A Miniature of Rt. Hon. Charles, Earl Cornwallis, K.G., 1794, watercolor on ivory, 3 in. (7.6 cm) high, sold at Sotheby’s “A Collection of Fine Continental Portrait Miniatures and Important English Miniatures,” London, November 27, 1972, lot 169; Attributed to John Smart, Miniature Portrait of Charles, 1st Marquis Cornwallis, 1792–1795, watercolor on ivory, 2 5/8 x 2 1/8 in. (6.7 x 5.4 cm), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2006-83. It is likely this work is actually by Samuel Andrews. The sash does indeed outline Cornwallis’s generous belly, and the white stock: A type of neckwear, often black or white, worn by men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. emphasizes his double chin. Smart also captures Cornwallis’s uneven eyes, the result of an injury he sustained while playing hockey at Eton College, when a classmate hit him in the eye, causing a “slight but permanent obliquity of vision.”10Correspondence of Charles, 1:3. The fellow classmate was Shute Barrington, later Bishop of Durham. While the injury likely did not detract from his ability on the battlefield, it may have attracted unwanted attention and contributed to his embarrassment about his looks.

Smart’s artistic skills helped to humanize Cornwallis’s imperfections while still documenting a man of great military and civic prowess—not only through his nine watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. portraits on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. and paper (Fig. 2) but also in print form. Smart transformed his portraits of military leaders into engravings, a collaboration with his former pupil Robert Bowyer (English, 1758–1834) and friend Robert Smirke (English, 1753–1845).11See George Noble and James Parker, after Robert Smirke and John Smart, Commemoration of the 11th October 1797, published 1803, line engraving, published by Robert Bowyer and John Edwards, 27 1/8 x 17 3/4 in. (68.9 x 45.2 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D15178. The engraving includes a portrait of Admiral Wells, whose miniature by Smart is also in the Starr Collection. Cornwallis’s illustrious life as soldier and statesman made him the perfect subject for Smart. While it remains unclear who commissioned the nine miniatures, dated 1786, 1787, and 1791–1794, all are rendered with faithful realism and accuracy.12The present miniature could have been intended as a gift to a political figure, friend, or loved one. A 1792 portrait was gifted to the Indian ruler Tipu Sultan; see Thomas Twining, Travels in India a Hundred Years Ago (London: James R. Osgood, 1893), 66. A 1794 miniature was given to Rawson Hart Boddham, Governor of the Bombay Presidency, as a memento of friendship, according to Sotheby’s, “A Collection of Fine Continental Portrait Miniatures and Important English Miniatures,” London, November 27, 1972, lot 169. Cornwallis’s bodily discomfort is not visible in the Nelson-Atkins portrait, replaced by a seemingly confident lieutenant general in his lustrous uniform.

Notes

-

“Cornwallis, Charles, first Marquess Cornwallis,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 13:474. Cornwallis was born on December 31, 1738, to Charles, 5th Baron Cornwallis, later 1st Earl Cornwallis and Viscount Brome (1700–1762), and Elizabeth Townshend (1703–1785). Cornwallis married Jemima Tullekin (née Jones, 1747–1779), daughter of Regimental Colonel James Jones, in 1768, and they had two children: Charles, later Viscount Brome (1774–1823), and Mary (1769–1840).

-

Cornwallis sat for other miniaturists, including Hugh Douglas Hamilton (Irish, ca. 1740–1808) in 1772, Diana Hill (English, ca. 1760–1844) in 1786, and William Grimaldi (English, 1751–1830) in 1810. See Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Portrait of General Charles Cornwallis, ca. 1770, pastel, 9 x 7 in. (22.9 x 17.8 cm), previously in the inventory of Philip Mould Ltd., London; Diana Dietz Hill, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1786, watercolor on ivory, 4 1/8 x 3 1/4 x 3/16 in. (10.5 x 8.3 x 5 cm), Mount Vernon Museum, H-4912, https://emuseum.mountvernon.org/objects/11032/charles-cornwallis-1st-marquess-cornwallis?ctx=31423f888d24e6becbc717c86e934ccf83be75c5&idx=0; William Grimaldi, Charles, 2nd Earl and 1st Marquess Cornwallis, ca. 1792–1798, 5 3/8 x 4 5/16 in. (13.6 x 10.9 cm), Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420856, https://www.rct.uk/collection/420856/charles-2nd-earl-and-1st-marquess-cornwallis-1738-1805. There is also a portrait of Cornwallis by Samuel Andrews (Irish, 1767–1807), but this is a copy after one of Smart’s portraits. See Attributed to Samuel Andrews, after John Smart, Portrait of Charles, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, ca. 1792, dimensions unknown, watercolor on ivory, Sotheby’s “Old Master Paintings” London sale, October 27, 2015, lot 603, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/old-master-paintings-l15035/lot.603.html.

-

For more on Cornwallis in the American Revolution, see Thomas Fleming, The Perils of Peace (New York: Dial Press, 1970), 16; Jerome Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2005), 294–97; David McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 146–48, 156–57, 191, 262.

-

“Cornwallis, Charles, first Marquess Cornwallis,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 13:474; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: The Imperial Years (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 17–18. Cornwallis held the titles until 1793. He was later appointed Commander-in-Chief and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1798, an office he held until 1801, and one he did not particularly enjoy: “The life of a Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland comes up to my idea of perfect misery, but if I can accomplish the great object of consolidating the British Empire, I shall be sufficiently repaid,” according to Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis, ed. Charles Ross (London: John Murray, 1859), 2:358. He was reappointed Lord Lieutenant of India in 1805 but died soon after his arrival and is buried on the banks of the Ganges at Ghazipur.

-

Smart worked in India from 1785 to 1795.

-

James Talboys Wheeler, India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal and Burma (New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1899), 2:489. Despite Cornwallis’s success in Seringapatam, his image was still represented satirically in the press. In James Gillray’s The Coming-On of the Monsoons; —or—The Retreat from Seringapatam, 1791, hand-colored etching, 8 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (22.3 x 27.5 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D13008, Cornwallis is depicted fleeing the battle of Seringapatam on donkey, with the inscription “What’s the matter, Falstaff?”, a reference to William Shakespeare’s overweight and comedic character.

-

The Nelson-Atkins portrait was likely in the collection of Jeffery Ludlam Barton Whitehead (1831–1915), who first lent the miniature to the Royal Academy’s Winter Exhibition in 1879; see Royal Academy of Arts, Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School, Including Oil Paintings, Miniatures, and Drawings: Winter Exhibition (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1879), 10:65, no. 23, as Charles, 1st Marquis of Cornwallis. The same miniature was likely sold at Christie’s “Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu, Watches, Miniatures, and Coins,” London, November 13, 1950, lot 89, as Portrait of Charles 1st Marquis Cornwallis, and shortly after acquired by the Starrs.

-

Correspondence of Charles, 1:247. The letter was sent from Calcutta and dated December 28, 1786. See George Charles Williamson, The History of Portrait Miniatures (London: G. Bell, 1904), 2:2, plate 70. His embarrassment about the blue ribbon may explain why he is depicted wearing it in William Grimaldi’s portrait of Cornwallis, and not as prominently in Smart’s. See Grimaldi, Charles, 2nd Earl and 1st Marquess Cornwallis, the Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420856.

-

Smart painted the Nawab at least twelve times. John Smart, Portrait Miniature of Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1786, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm) high, previously in the inventory of Philip Mould Ltd., London; John Smart, Portrait of Charles Marquis Cornwallis, 1787, sold at Christie’s “Catalogue of Old Sèvres Porcelain, Old English Miniatures, Old French Gold and Enamel Boxes, Watches, and Objects of Vertu, Bronzes and other Objects of Art,” London, May 15, 1903, lot 28; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1791, watercolor on ivory, 2 3/4 in. (7 cm) high, sold at Christie’s “Centuries of Style: Silver, European Ceramics, Portrait Miniatures and Gold Boxes,” London, November 27, 2012, lot 393; John Smart, Charles, 1st Marquis Cornwallis, 1792, watercolor on ivory, 2 3/8 in. (6 cm) high, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 3922; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, 1792, pencil and gray wash, 7 1/4 x 6 5/8 in. (18.4 x 16.8 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 4316; John Smart, Charles Cornwallis, 1793, watercolor on ivory, unknown dimensions, previously in the inventory of Elle Shushan; John Smart, A Miniature of Rt. Hon. Charles, Earl Cornwallis, K.G., 1794, watercolor on ivory, 3 in. (7.6 cm) high, sold at Sotheby’s “A Collection of Fine Continental Portrait Miniatures and Important English Miniatures,” London, November 27, 1972, lot 169; Attributed to John Smart, Miniature Portrait of Charles, 1st Marquis Cornwallis, 1792–1795, watercolor on ivory, 2 5/8 x 2 1/8 in. (6.7 x 5.4 cm), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2006-83. It is likely this work is actually by Samuel Andrews.

-

Correspondence of Charles, 1:3. The fellow classmate was Shute Barrington, later Bishop of Durham.

-

See George Noble and James Parker, after Robert Smirke and John Smart, Commemoration of the 11th October 1797, published 1803, line engraving, published by Robert Bowyer and John Edwards, 27 1/8 x 17 3/4 in. (68.9 x 45.2 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D15178. The engraving includes a portrait of Vice Admiral Wells, whose miniature by Smart is also in the Starr Collection.

-

The present miniature could have been intended as a gift to a political figure, friend, or loved one. A 1792 portrait was gifted to the Indian ruler Tipu Sultan; see Thomas Twining, Travels in India a Hundred Years Ago (London: James R. Osgood, 1893), 66. A 1794 miniature was given to Rawson Hart Boddham, Governor of the Bombay Presidency, as a memento of friendship, according to Sotheby’s, “A Collection of Fine Continental Portrait Miniatures and Important English Miniatures,” London, November 27, 1972, lot 169.

Provenance

Probably Jeffery Ludlam Barton Whitehead (1831–1915), Kent, England, by 1879–at least 1891 [1];

With an unknown owner, by November 13, 1950 [2];

Purchased from the unknown owner’s sale, Objects of Art and Vertu, Watches, Miniatures, and Coins, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, November 13, 1950, lot 89, as Portrait of Charles 1st Marquis Cornwallis, by James, 1950 [3];

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] Whitehead lent a portrait to the Royal Academy’s Winter Exhibition in 1879. Jeffery was a banker and member of the Stock Exchange and an avid collector of portrait miniatures. However, his sale of miniatures did not include the present portrait, see Catalogue of Ancient and Modern Pictures and Drawings; the Property of Jeffery Whitehead, Esq., Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, August 6, 1915.

The portrait of Cornwallis once owned by Whitehead is the only version whose location today remains unknown, increasing the likelihood that the same portrait is the one now in the Starr Collection. The date, description, and size also increase the probability of its Whitehead provenance.

[2] In the Christie’s November 13, 1950, sale, “Different Properties” sold lots 66–101.

[3] It was described in the sales catalogue as, “Portrait of Charles 1st Marquis Cornwallis—by John Smart, signed with initials and dated 1792–three-quarter face to the left in scarlet military coat with blue facings and gold epaulettes, wearing the badge and ribbon of the Garter–oval, 2 3/4 in. high.” The catalogue for this sale is located at University of Missouri-Kansas City, Miller Nichols Library. According to the annotated catalogue, “James” bought lot 89 for “125.” Art Prices Current (1950–1951) confirms that “James” bought lot 89 for £131 5s.

Exhibitions

Probably Exhibition of Works by The Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School, including Oil Paintings, Miniatures, and Drawings, Royal Academy, London, Winter Exhibition, 1879, case P, no. 23, as Charles, 1st Marquis of Cornwallis.

Probably Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures, Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, 1889, case X, no. 24, as Charles, Marquess Cornwallis.

Probably Exhibition of the Royal House of Guelph, The New Gallery, London, 1891, case J, no. 974, as Charles, 1st Marquess Cornwallis.

John Smart, Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Charles, 2nd Earl of Cornwallis.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 125, as Charles, 2nd Earl of Cornwallis.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis.

References

Royal Academy, Exhibition of Works by The Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School, Including Oil Paintings, Miniatures, and Drawings, Winter Exhibition (London: William Clowes and sons, 1879), 65, case P, no. 23, as Charles, 1st Marquis of Cornwallis.

Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures (London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1889), 34, as Charles, Marquess Cornwallis.

Exhibition of the Royal House of Guelph (London: New Gallery, 1891), 170, as Charles, 1st Marquess Cornwallis.

Catalogue of Objects of Art and Vertu, Watches, Miniatures, and Coins, (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, November 13, 1950), lot 89, as Portrait of Charles 1st Marquis Cornwallis.

Antiques 90 (July–December 1966): 356, fig. 10, (repro.), as Charles, first Marquis and second Earl Cornwallis.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 125, pp. 31, 44, (repro.), as Charles, 2nd Earl of Cornwallis.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.