Citation

Chicago:

Blythe Sobol, “John Smart, Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1581.

MLA:

Sobol, Blythe. “John Smart, Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1581.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

Read more about this object at the associated catalogue entry.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Stephanie Spence and John Twilley, “John Smart, Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787,” technical entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1581.

MLA:

Spence, Stephanie, and John Twilley. “John Smart, Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787,” technical entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1581.

Along with many of his contemporaries, John Smart transitioned to larger ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. supports near the end of the eighteenth century.1As technical expertise improved during the eighteenth century, miniaturists became more skilled at painting on ivory and overcoming its adverse qualities. Thus, the size of ivory supports grew from one and a quarter inch in the midcentury to as much as three and a quarter inches by the end of the century. John Murdoch et al., The English Miniature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 20, 80, 177. The 2 1/4-inch-high miniature portrait of newlywed Charlotte Porcher (née Burnaby) is one such example. The painting depicts Mrs. Porcher in three-quarters view with voluminous lilac-tinted hair wearing a white dress with blue trim set before a blue-gray sky. The portrait is signed in the lower left “J.S./1787/I,” with the letter “I” indicating it was painted while Smart lived abroad in India.2Blythe Sobol, “John Smart at Home and Abroad: Colonialism in Miniature: John Smart in India, 1785–1795,” in this catalogue.

The unusual color of Charlotte Porcher’s hair is shared with eleven other sitters in the Nelson-Atkins collection as well as others in his larger corpus of works.3See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue. Pink or lilac hair powder was uncommon in portraiture, with most subjects opting for white or grayish-white. However, Smart’s portraits of his merchant-class clientele reveal hints of pink and lilac hues, raising the question of whether this was a deliberate choice or the result of light-sensitive pigments fading over time, obscuring their original effect.

Pigment analysis and technical imaging were performed on four John Smart portraits with light pink or lilac-tinted hair, spanning a twenty-five-year period of his career, to explore the artist’s palette and working techniques beyond the means of visual examination.4See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.,5The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analyses was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It is important to note that the very small scale and extreme thinness of the paint applications in portrait miniatures require that analysis be done to the extent possible through non-sampling means, such as x-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of x-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method.. However, no single analytical method provides a complete pigment analysis. Instead, pigment identification requires that information from different scientific techniques be combined and interpreted. This includes microanalytical methods, like scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDS): A combined technique that uses a scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy to analyze materials. Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an x-ray spectrometer so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., that provide powerful means of extracting information from minute samples as small as single particles that cannot be obtained by non-sampling methods. Technical imaging is a useful tool that can allow inferences to be drawn based on optical behaviors such as fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. Also known as ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence. colors and can be used as a complementary method to analytical techniques.6Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging set included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can be used to make inferences about artists’ materials and to visualize restoration materials such as inpainting, varnish coatings, and materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an art work and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis. While these methods were used to find answers pertaining to the sitters’ hair color, they also offered insights into the full compositions, revealing new information about John Smart’s palette and working techniques that were previously unknown. The results of this study, summarized in Table 1, are discussed in further detail below.

| Feature | Visible Color(s) | Inferred Partial Color Palette |

|---|---|---|

| Hair | Pink Brown Blue White |

Iron oxide pigments Natural ultramarine* Ivory support |

| Facial features | Red/pink Blue White |

Iron oxide pigments Natural ultramarine* Ivory support |

| Dress | White | Ivory support |

| Blue trim | Blue White |

Azurite Natural ultramarine Lead white |

| Background | Blue | Natural ultramarine |

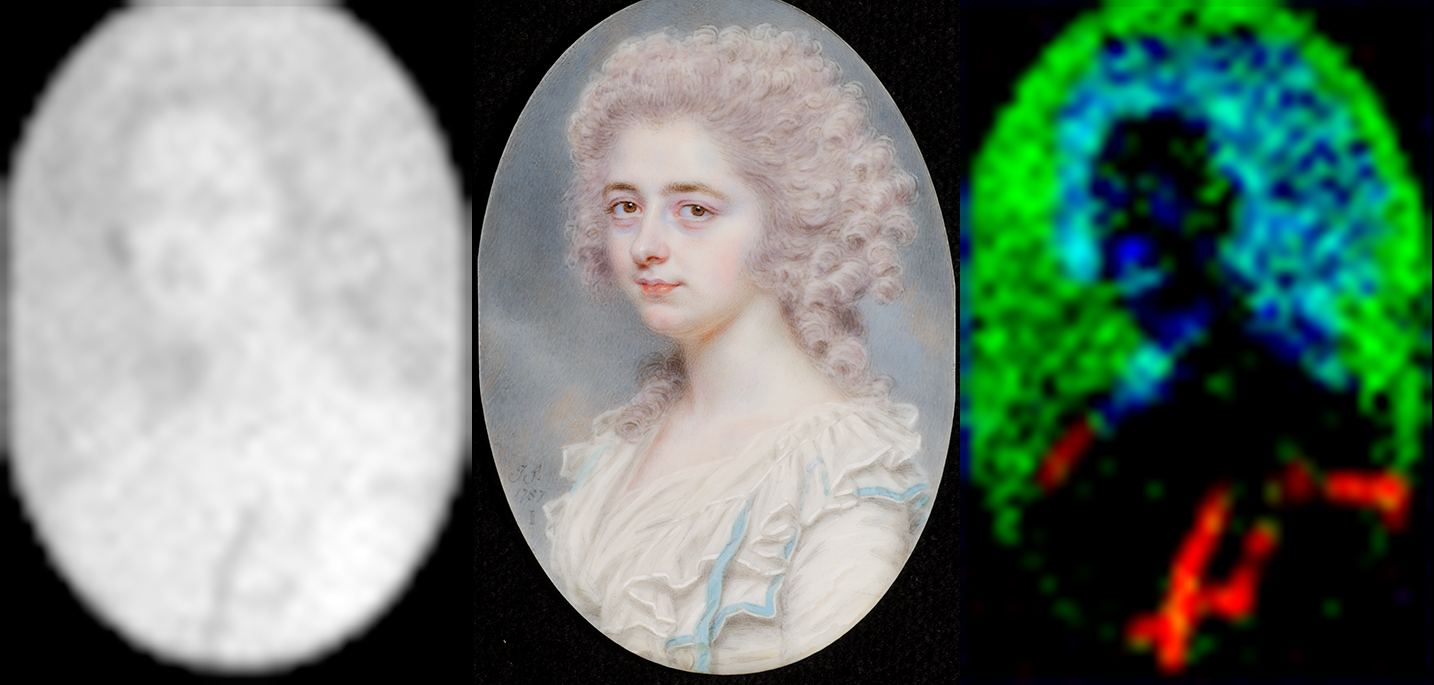

Among the four portraits analyzed, the artist differentiated the means of painting based on the gender of the sitters. The fair complexions of the female depictions rely more heavily on the whiteness and translucence of the ivory support and are therefore more thinly painted than those of the males, whose ruddy complexions required the ivory to be more heavily painted. This difference also extends to the representations of their clothing and becomes quite apparent in MA-XRF, where the response from the thin paint of the female portraits is weak and indicative of only the most abundant pigments. All portraits give strong maps for calcium and phosphorous, the two primary elements of bone, tooth enamel, and ivory. The phosphorous response is suppressed where the overlying paint absorbs some of its characteristic x-rays, giving a faint “negative” image of the sitter where the heavier paint applications have blocked the response from weaker x-rays (Fig. 1). In contrast, the male sitters have large areas of the phosphorous map fully blacked out due to heavier paint applications.

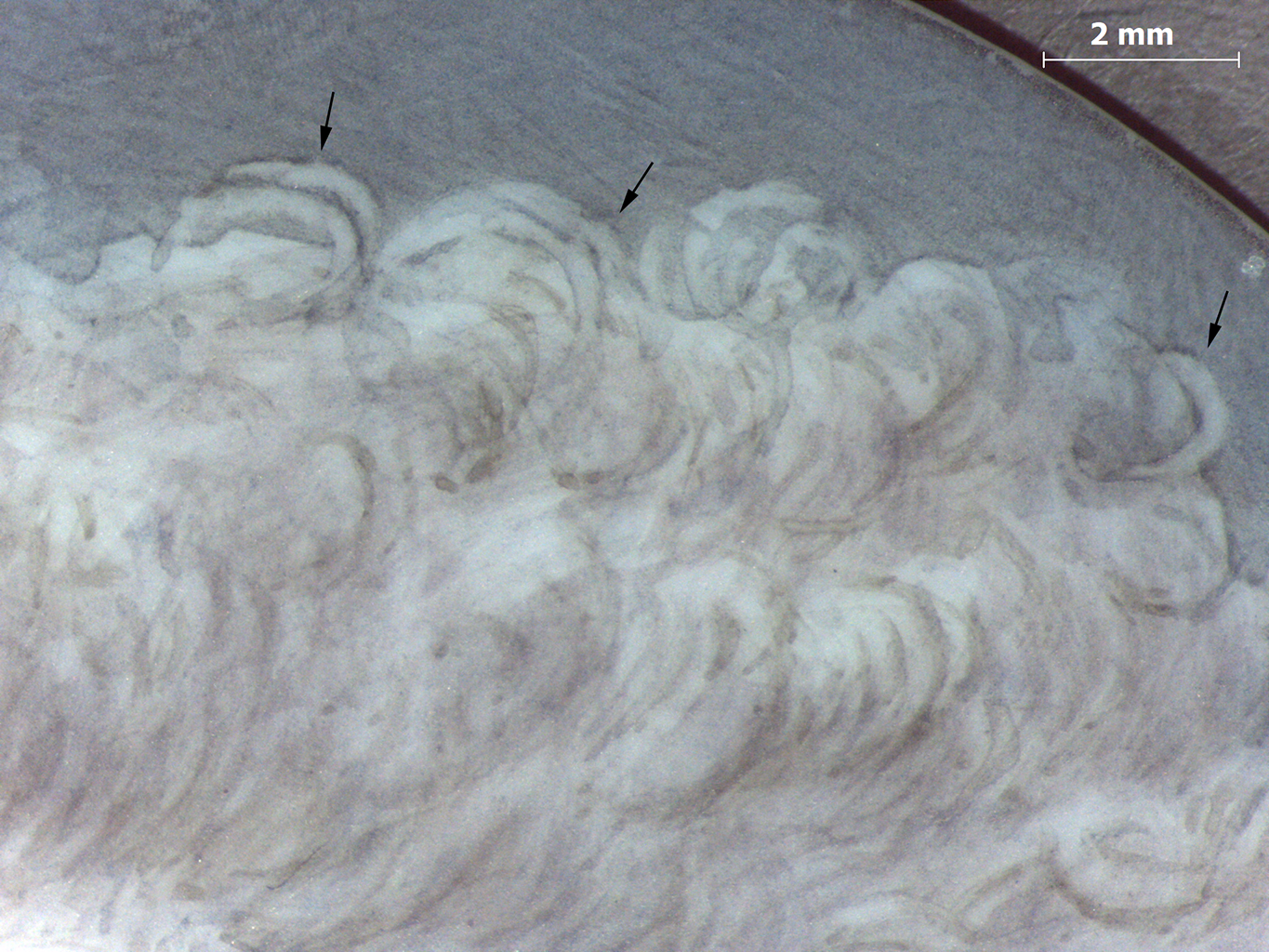

Mrs. Porcher wears her lilac-tinted hair in the wide,

frizzled: A form of tightly curled hair

fashionable in the latter half of the eighteenth

century.

hairstyle of the period, with curly tendrils trailing

down her back and draping over her right

shoulder.7Smart’s portrait of Mrs. Ann Chase, painted in

India a year later in 1788, features Mrs. Chase

with matching hairstyle and hair color to that of

Charlotte Porcher. Both portraits show the

proclivity for the frizzled hairstyle among women

of the period, as well as similarities in their

dress and in Smart’s rendering of the lips.

John Smart, Ann Chase (née Rand), 1788,

watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.5 cm) high,

Philip Mould, London,

https://philipmould.com

The false-color infrared (FCIR): Images created through digital post-processing by combining and rearranging the color channels of visible and near-infrared images. In the visible image, the Red and Green channels are assigned to the Green and Blue channels respectively, while the infrared image is assigned to the Red channel. The false colors produced can aid in interpretation of media and materials present and inform further scientific analysis, conservation examination, and scholarly research. image presents similarities between the pigment composition of the hair color in the male and female portraits. Both Charlotte Porcher and the sitter in Portrait of a Man, 1773 (F65-41/11) have lilac-tinted hair in visible light that appears pink in FCIR (see Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, the pink-haired sitters Mrs. Ronalds (F65-41/39) and the gentleman in Portrait of a Man, 1778 (F65-41/19) present as yellow in their respective false-color images. This visual similarity in the false-color images of Charlotte Porcher and the male portrait, painted fourteen years apart, is substantiated with elemental analysis where the pink false-color is indicative of ultramarine identified in the hair with SEM and MA-XRF.8Pure ultramarine in gum arabic appears red in false-color IR. The pink tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is due to the pigment mixture that has been found to contain ultramarine and iron-based pigments. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the pigments that influence the false color appearance—explains why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007. While the appearance of the hair in false-color is heavily influenced by iron earth pigments, the pink FCIR behavior of the background is also strongly suggestive of the role of ultramarine. In this case, iron plays no role in the blue mixture. A comparison of the elemental maps for copper, sulfur, and iron in an RGB overlay demonstrates where iron (blue) and sulfur (green) are in mixture (see Fig. 1).

The MA-XRF map for sulfur hints at the important role played by ultramarine in this painting. Of the four elements comprising ultramarine—sodium, silicon, aluminum, and sulfur—only the sulfur is mappable for such dilute paint. Moreover, because sulfur is not uniquely associated with ultramarine, other means were employed for its confirmation. SEM examination of minute samples revealed individual particles of crushed, natural lapis lazuli. All of the constituent elements of this natural form of ultramarine were confirmed to be present through x-ray spectrometry carried out with SEM, establishing that ultramarine was used throughout the hair and background.

An alternative theory to the purposeful choice of lilac color is the fading of some light-sensitive pigment in a mixture that would originally have given the sitter a natural hair color such as brown. Examination of pigment particles from the hair with SEM-EDS did not reveal any examples of alumina-based lakes, nor of lakes precipitated on any other compound, that would explain fading of a natural hair color to the lilac color seen today. It remains possible that an organic dye: A natural colorant made from complex organic compounds extracted from plants, animals, insects, lichens, and shellfish. As most natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore must be painted directly onto the surface. Organic dyes can be further processed and precipitated onto an inorganic substrate to produce a lake pigment. See also lake pigment. with yellow, green, or brown color, in soluble form rather than as a lake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used., was once present along with the surviving inorganic pigments to produce a more natural hair color.9Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped with MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was directed to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases with SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

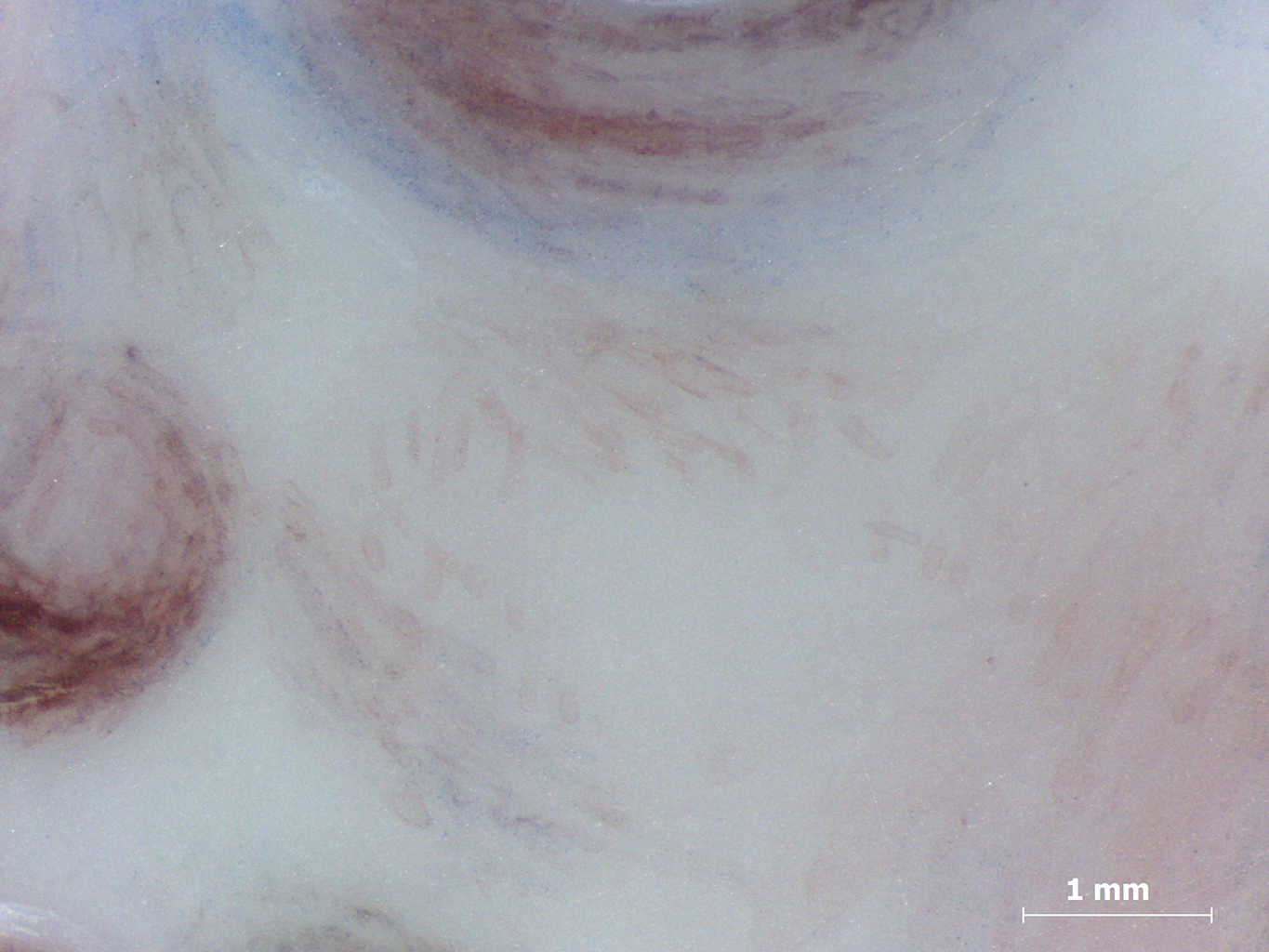

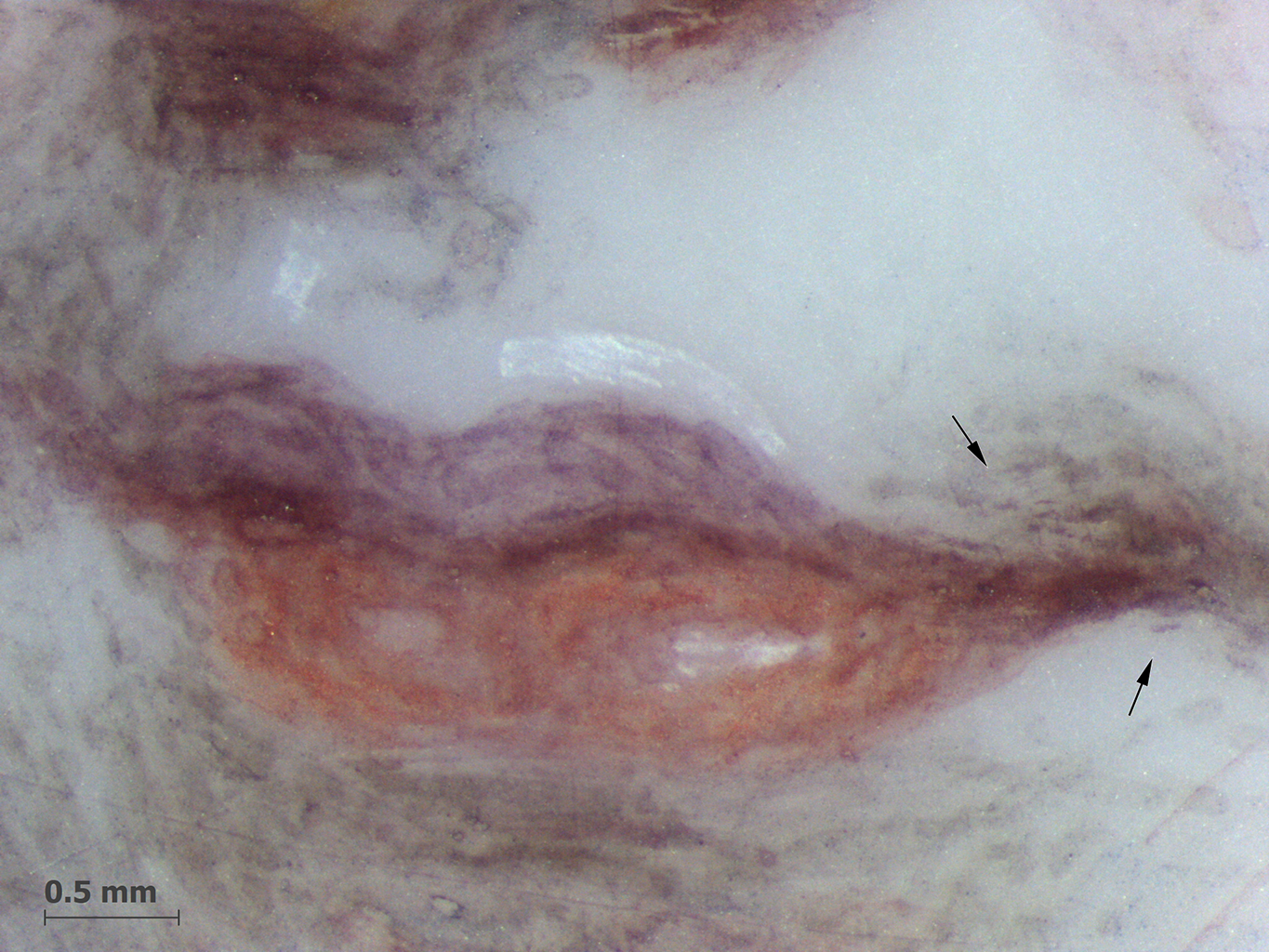

The sitter’s porcelain skin would nearly merge with her white dress were it not for the pink tint of her neckline. The luminous quality of the ivory lends itself to the sitter’s pallor, and Smart capitalized on this characteristic by relying on the ivory as the base color in his depiction of the flesh tones. Red, magenta, blue, and gray-brown colorants are used for the midtones and shading, which rely heavily on the iron earth pigments in the form of ochers and siennas disclosed in MA-XRF. These denser areas of color use a combination of hatching and stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. to prevent a muddied appearance (Fig. 4). Thin washes of blue were applied in such a dilute manner that individual pigment particles are visible under magnification. As with the hair, the presence of blue particles in the flesh colors that lack a response for copper in MA-XRF demonstrates that ultramarine is used in the pale skin, even though the amounts are too low for the sulfur to be mappable in these areas. This use of blue colorant makes the whites appear whiter, exaggerating the porcelain-like quality of the sitter’s skin. Single strokes of opaque white capture the brightest highlights along the nose and around the eyes, pupils, and lips. Delicate lines of sgraffito are used sparingly in the facial features, outlining the chin, lower lip, and left nostril.

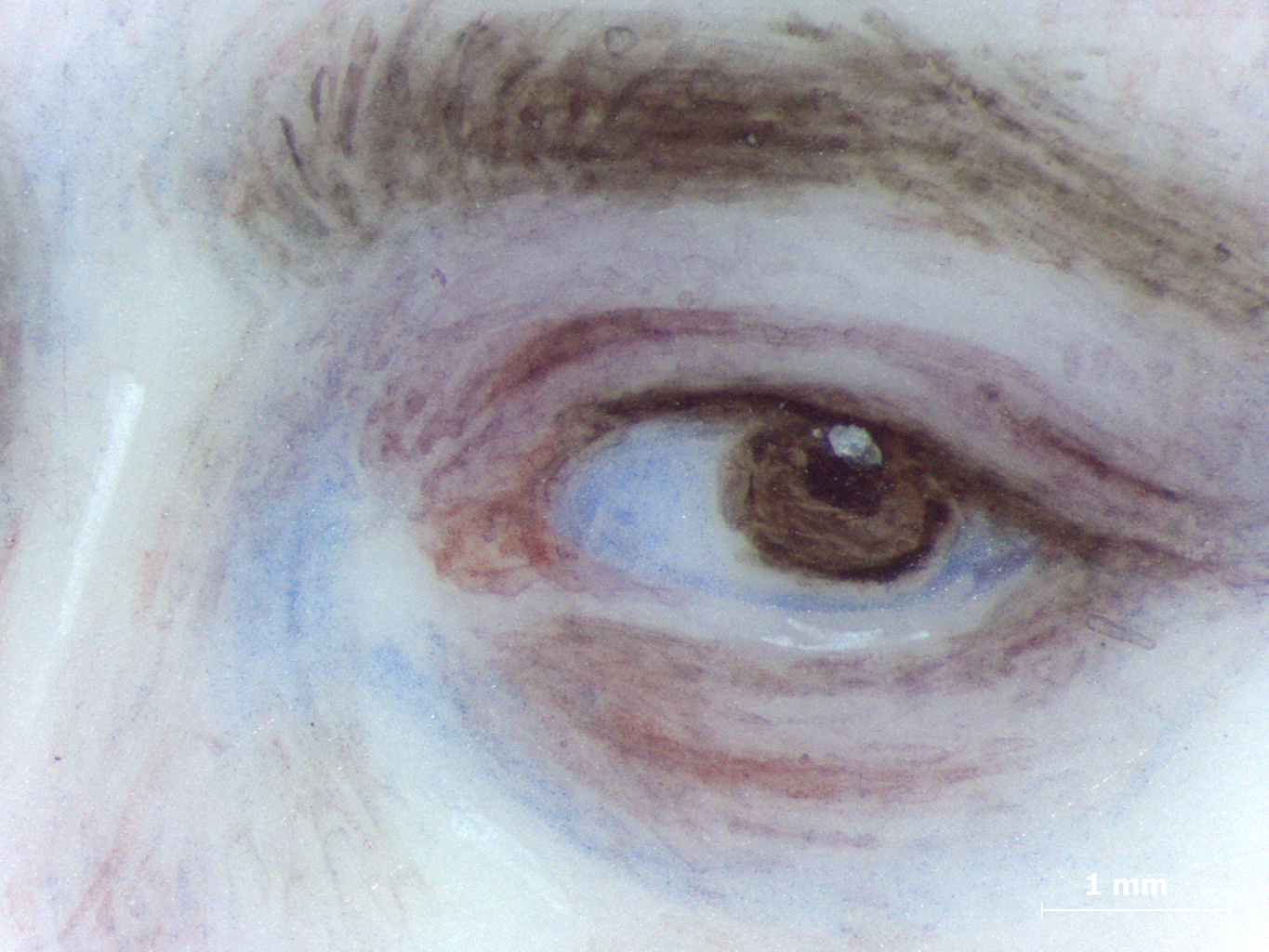

Charlotte Porcher’s pale complexion is accentuated by her wide brown eyes, thick brows, and the bold color of her large, full lips. White impasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. highlights have been added in the pupils. Applications of opaque, dark brown paint outline the pupils and upper lash line. The eyelashes are painted on the outer edge of the right eye only. The whites of the eyes are heavily pigmented with ultramarine blue, adding contour and enhancing their whiteness. Stippling in the magenta shadows around the woman’s eyes is visible under magnification (Fig. 5). Her dark brows are carefully painted with blunt, directional hatching in a style that contrasts with the dilute paint application used to create her pale, porcelain skin.

As with Smart’s other portraits, the sitter’s upper lip is magenta, while the lower lip is a rosy-red tone. Stippling brushstrokes, visible under magnification, show a thick application of each color (Fig. 6). The red pigment on the lower lip has a grittier texture, similar in nature to the blue wash in her face. Bare ivory and opaque white pigment create the two highlights on her lower lip. There is also a highlight along the lip line and along the philtrum: The vertical groove between the base of the nose and the border of the upper lip.. Smart used sgraffito in the corner and under her lower lip to reshape her mouth.

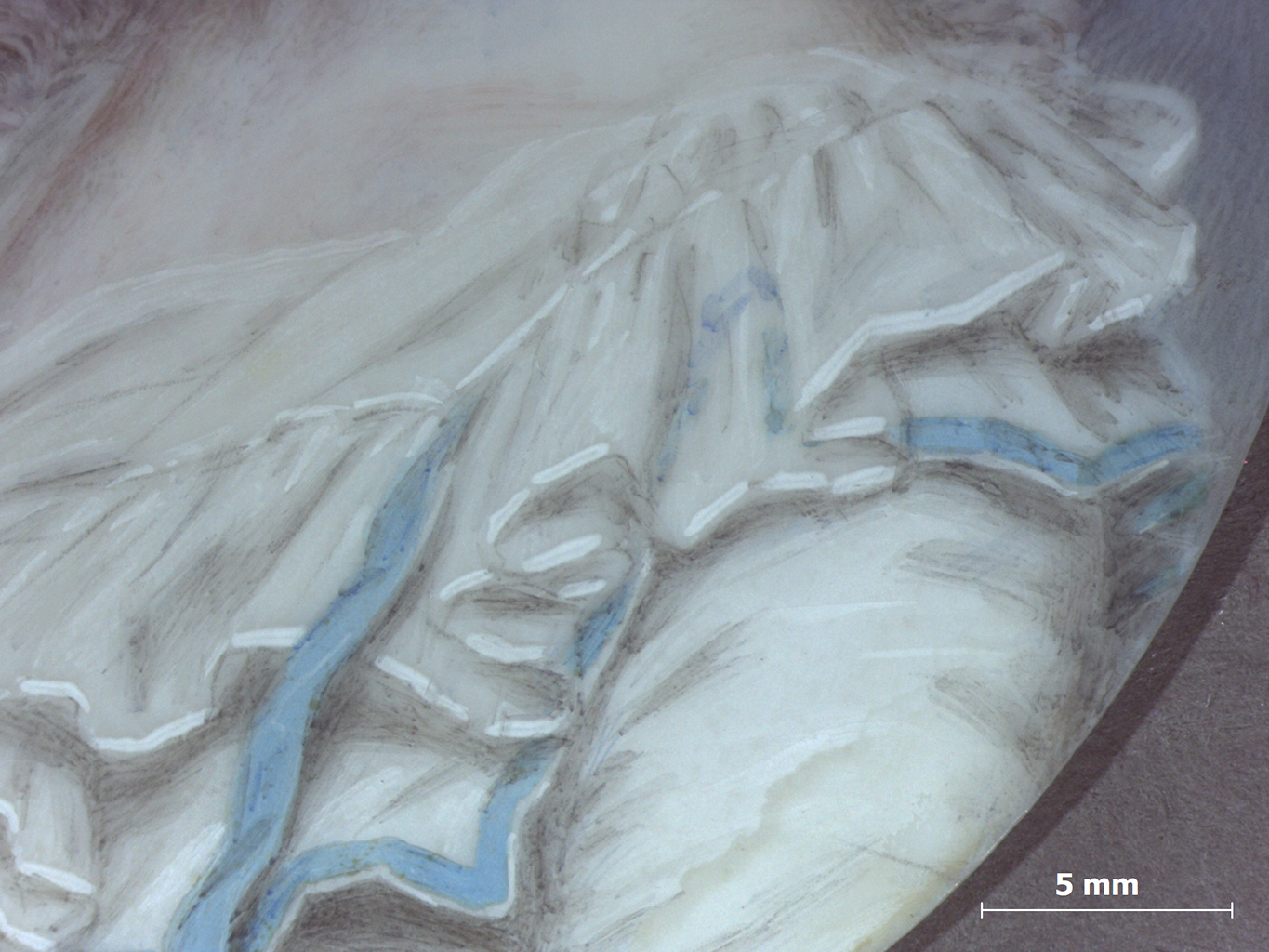

Mrs. Porcher’s white chemise dress has a sketchy quality. Smart’s graphite underdrawing defines the delicately flowing drapery and layers of ruffles (Fig. 7). The dress is open at the neckline, with blue drawstrings hanging loose down the front. As with her skin, ivory is used as the base color, helping to create the light and airy fabric favored by British colonialists in India at the time.10Smart depicted another sitter wearing a dress almost identical to Mrs. Porcher’s only a year earlier in 1786; see Portrait of a Woman (1786), F65-41/27. The delicate chemise has two layers of ruffles with blue ribbon accents. Translucent ivory accentuates the sheerness of the top ruffle, while thick white lines and dark shading along the edge define the separation between the two layers. Only the lower ruffle is accented with light blue trim, which was created with an opaque mixture of lead white and azurite blue. Shading and contouring of the trim are rendered with brushstrokes of black and transparent blue color. Smart’s talent for capturing even the smallest details is on display in his treatment of the blue trim on Mrs. Porcher’s left shoulder. Here, a small section of trim passes under the sheer fabric of the top ruffle. Smart reveals this segment of the trim by using short, overlapping brushstrokes of a transparent blue pigment, providing continuity and three-dimensionality to the garment (Fig. 8). The transparent pigment is visually similar to the blue used in the sitter’s face and hair. The XRF map for sulfur correlates to these areas of blue, indicating that the ultramarine was also used in localized areas of shading in the dress.

The blue trim is strongly depicted in the map for copper, demonstrating that this blue must be based on a mineral pigment or a synthetic version of one, such as blue verditer. SEM examination of pigment particle shape confirmed natural azurite rather than synthetic blue verditer. The map for lead also correlates to portions of the trim, demonstrating a mixture of lead white and azurite to render the light blue color. The purple color of the trim in the FCIR image also implies the presence of azurite (see Fig. 3a).11See Figure 9,“Flowchart for the identification of blue pigments by multispectral imaging,” in Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method.” Note that identification of pigments by inference from multispectral imaging (MSI) should follow a flowchart that relies on more than one image to make an identification. In the case of the blue trim in Charlotte Porcher’s portrait, the ultraviolet reflected (UVR) and IR images also confirm that the blue color is likely azurite in mixture with a white pigment, resulting in the purple color visible in FCIR. See also Dyer and Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano Egyptian‑ Funerary Portraits at the British Museum;” and Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment.” Areas where ultramarine has been incorporated into the trim for contouring appear more reddish in FCIR. The treatment of the blue trim in this portrait contrasts with the blue mixture Smart used in his later portrait of Mrs. Ronalds (F65-41/39), where her blue sash is pink in FCIR and ultramarine was identified in the pigment mixture.

The background deviates from the gray or brown color of other portraits by Smart with a depiction of a muted sky painted in gray, blue, and pink. This change in approach to the background is apparent in the marked difference in usage of iron earth pigments in the two female portraits for which elemental mapping was conducted. The hair and the skin shadows of both sitters rely heavily on iron earths. They are also used for the background of the 1798 Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds (F65-41-39) but play no role in the blue background here. Instead MA-XRF demonstrates that ultramarine was heavily used for the blue shades (see Fig. 1).

The portrait miniature is housed in a two-part gilt copper alloy case. The inner case, or insert, housing the miniature and two paper backing cards, is an unadorned, copper alloy case with a thin, gilt copper bezel: A groove that holds the object in its setting. More specifically, it refers to the metal that holds the glass lens in place, under which the portrait is set. holding the curved glass lens. The insert has a flat back and pressure-fits inside the outer case. The outer case is also gilt copper with brightwork: A type of decorative engraving used on metal objects that is created by making a series of short cuts into the metal using a polished engraving tool that causes the exposed surfaces to reflect light and give an impression of brightness.. A small, oval hair reserve with a decorative gold monogram of the sitter’s initials, C. P., is protected with cover glass. The hair art: The creation of art from human hair, or “hairwork.” See also Prince of Wales feather. is braided, brunette hair glued to a paper backing card.

Prior to conservation treatment, a moderate layer of mold had formed inside the case, and the interior of the glass had a dirty surface film. Yellow tidelines at the bottom of the portrait indicated that water had penetrated the case, resulting in discolored staining now visible on the paint surface. Areas of paint loss in the white dress are visible along the edge of the ivory support.

The results of analyses of this corpus of John Smart miniatures extend beyond the peculiarity of the sitters with light pink and lilac-tinted hair, revealing previously unknown information about Smart’s palette. Comparisons of the four portraits spanning a twenty-five-year period of Smart’s career both in London and India have brought to light ways in which he innovated beyond methods described in contemporaneous painting treatises. Additionally, they illuminate pronounced differences in his approach to representation of male and female sitters. While the analyses do not reveal lake pigments in the hair and fail to account for a color change there, the possibility remains that now-faded organic dyes, not detectable by these methods, could account for a color change. XRF elemental mapping used in conjunction with SEM-based elemental analysis has provided pigment identifications for part of the palette. Complementary information from additional analytical steps holds the potential for a comprehensive understanding of John Smart’s palette to be derived from the extensive holdings of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Notes

-

As technical expertise improved during the eighteenth century, miniaturists became more skilled at painting on ivory and overcoming its adverse qualities. Thus, the size of ivory supports grew from one and a quarter inch in the midcentury to as much as three and a quarter inches by the end of the century. John Murdoch et al., The English Miniature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 20, 80, 177.

-

Blythe Sobol, “John Smart at Home and Abroad: Colonialism in Miniature: John Smart in India, 1785–1795,” in this catalogue.

-

See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue.

-

See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.

-

The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analyses was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging set included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can be used to make inferences about artists’ materials and to visualize restoration materials such as inpainting, varnish coatings, and materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an artwork and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis.

-

Smart’s portrait of Mrs. Ann Chase, painted in India a year later in 1788, features Mrs. Chase with matching hairstyle and hair color to that of Charlotte Porcher. Both portraits show the proclivity for the frizzled hairstyle among women of the period, as well as similarities in their dress and in Smart’s rendering of the lips. See John Smart, Ann Chase (née Rand), 1788, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 in. (6.5 cm) high, Philip Mould, London, https://philipmould.com/content/feature/1727/detail/artworks5637/.

-

Pure ultramarine in gum arabic appears red in false-color IR. The pink tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is due to the pigment mixture that has been found to contain ultramarine and iron-based pigments. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the pigments that influence the false-color appearance—explains why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007.

-

Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped with MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was directed to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases with SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

-

Smart depicted another sitter wearing a dress almost identical to Mrs. Porcher’s only a year earlier in 1786; see Portrait of a Woman (1786), F65-41/27.

-

See Figure 9, “Flowchart for the identification of blue pigments by multispectral imaging,” in Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method.” Note that identification of pigments by inference from multispectral imaging (MSI) should follow a flowchart that relies on more than one image to make an identification. In the case of the blue trim in Charlotte Porcher’s portrait, the ultraviolet reflected (UVR) and IR images also confirm that the blue color is likely azurite in mixture with a white pigment, resulting in the purple color visible in FCIR. See also Dyer and Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano Egyptian‑ Funerary Portraits at the British Museum;” and Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment.”

Provenance

Elsie Gertrude Kehoe (1888–1967), Cliffe Dene, Saltdean, Sussex, England, 1950 [1];

Purchased from her sale, Objects of Vertu, Fine Watches, Etc., Including The Property of Mrs. W. D. Dickson; also Fine Portrait Miniatures Comprising The Property of Mrs. Kehoe, Sotheby’s, London, June 15, 1950, lot 175, as his wife, Charlotte, by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1950–1965 [2];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] Elsie Gertrude Noble married Bartle Charles Philip Kehoe (1886–1949) in 1913 in Salford, Lancashire. The couple lived at 29 Harrington Gds., South Kensington in 1927; 1 Royal Crescent, Marine Parade, Brighton in 1929; and Roedean Crescent, “Four Winds” in 1939. Bartle’s job was “managing director public works contractor.” Elsie and Bartle traveled internationally; passenger lists show they traveled from Genoa, Italy, to Southampton in December 1927 and again in November 1929 (they were away for about a month in 1929). Bartle’s profession is also listed as, “Civil Engineer,” “Director,” and “Director Coy.” All according to records found on Ancestrylibrary.com. They do not appear to have had children. Bartle died November 2, 1949. According to his will, his effects were £10,665. See UK Probate Search: Kehoe, 1950, p. 26, https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk/. Elsie died at 60 Greenways Ovingdean, Brighton on December 16, 1967. Her effects totaled £9,738.

Martha Jane Starr’s correspondence to her friend, Betty Hogg, from March 22, 1949: “A Mrs. Kehoe is a collector over there [London] and I was referred to her last year and just recently she mailed me a catalogue from Agnew with the sale prices of miniatures paid and some fine ones went very reasonably in comparison with American prices. If the distance isn’t too great perhaps you could phone or contact her for her opinion on the numbers and portraits I’m listing.” An undated letter from Mrs. Hogg, following an auction “. . . your lots 25 and 48 had me worried they seemed so popular! I did not call Mrs. Kehoe for I thought she might be a competitor and bid against me!!” The Starrs mentioned them in Antiques magazine in 1961 (p. 440): “A Mr. and Mrs. Kehoe of Brighton gave us gracious hospitality while showing us theirs [collection of miniatures].” With thanks to Maggie Keenan for this research on Elsie Kehoe and untangling the relationship between Mrs. Kehoe and the Starrs, who considered themselves rival collectors.

[2] The joint lot of Charlotte Porcher and her husband Josias is illustrated and described in the catalogue as “a superb pair of miniatures, by John Smart, signed and dated 1787, of Josias Dupré Porcher and his wife, Charlotte, the former three-quarters sinister, powdered hair en queue, in white cravat and vest, and grey-brown coat; his wife three-quarters dexter, with a mass of curly hair falling to her shoulders, in a cream dress edged with pale blue, both with monograms at the back, narrow ovals, 2 3/8 in. . . . J. D. Porcher was Mayor of Madras in 1792, returned to England 1800, Member of Parliament for Bodmin, Bletchingley, and Dundalk, 1802–1818, Privy Councillor December, 1818; died Winslade House, near Exeter, April 25th, 1820. His wife, the second daughter of Admiral Sir William Burnaby, Bt., married J. D. Porcher at St. Mary’s, Fort St. George, Madras, on November 1st, 1787.” Archival research has shown that Leggatt Brothers served as purchasing agents for the Starrs. See correspondence between Betty Hogg and Martha Jane Starr, May 15 and June 3, 1950, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 118.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Charlotte Porcher.

References

Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 72.

Daphne Foskett, “Miniatures by John Smart: The Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum,” Antiques 90, no. 3 (September 1966): 356, (repro.).

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 118, p. 42, (repro.).

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.