Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Brummell, Probably Mary Brummell, 1785,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1570.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Brummell, Probably Mary Brummell, 1785,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1570.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

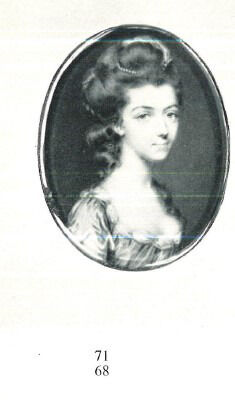

This miniature, initialed and dated “J.S. 1785” by the artist, entered the Nelson-Atkins collection as Miss Kendall in 1965, as part of the Starr family foundation gift.1It is uncertain where the name Kendall came from; however, in an inventory sheet from the Starr family, the portrait is identified as #215, Miss Kendall, and dated 1784. Scans in NAMA curatorial files. Six years later, with the publication of the collection handbook in 1971, it was demoted to “an Unknown Lady.”2The miniature was reproduced in a Nelson-Atkins publication “Exhibitions: Portrait Miniatures by John Smart,” Gallery Events (December 1965). The exhibition was held in the Burnap Ceramics Room, December 10–January 2, 1965. However, as part of the research undertaken for this catalogue, an inscription was discovered on the interior backing card, written in John Smart’s hand, that identifies the sitter as “Mrs. Brummell.”3The interior inscription reads “Mrs. Brommell”; however, Smart’s other portrait is clearly entitled “Brummell,” and it is the same sitter. This marks the second known portrait of Mrs. Brummell by Smart; the first is a watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. completed five years earlier (Fig. 1). Despite the five-year gap, the sitter’s hair and facial features appear remarkably unchanged, though her attire in the Nelson-Atkins miniature reflects more updated fashion. This continuity raises intriguing questions about Smart’s practice of dating and reusing preparatory sketches in his work.

John Smart was known to create and retain preparatory sketches for his miniatures on ivory, which he often used as the basis for later works. It is plausible that an untraced preparatory drawing served as the foundation for both the 1780 and 1785 portraits of Mrs. Brummell. In the earlier miniature, Sotheby’s auction house described Mrs. Brummell as wearing “an apple-green silk dress with pale blue sleeves, grey background,” with her “brown hair entwined with pearls, piled on her head with loose curls falling to her shoulder.”4Sotheby’s, London, “The Property of Dyson Perrins, Esq.,” May 14, 1959, lot 68. In the Nelson-Atkins version—which is a finished sketch, judging by Smart’s inscription and date—her expression, face, and hair remain nearly identical, though her dress is changed to a pale yellow-and-white gown set against a sky background. The similarities between the two suggest that Smart may have refined the details of dress and background while reusing the same preparatory sketch.

While Smart identified the sitter only as “Mrs. Brummell,” there is compelling evidence to suggest that she may be Mary Brummell, née Richardson (1754–1793), a celebrated beauty and daughter of the Keeper of the Lottery Office.5Philip Carter, “Brummell, George Bryan [known as Beau Brummell] (1778–1840),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, January 6, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/3771. In 1772, she married William Brummell, private secretary to Prime Minister Lord North, and the couple had three children, including George “Beau” Brummell, a pivotal figure in Regency: Part of the Georgian era, when King George III’s son ruled as his proxy, dating from approximately 1811 until 1820. fashion.6Carter, “Brummel, George Bryan [known as Beau Brummell].” A comparison between this miniature and a portrait of Mary Brummell by Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735–1811) from 1772, likely occasioned by her marriage, reveals striking similarities, including wide-set blue eyes, a widow’s peak, arched eyebrows, an elongated nose, and a thin upper lip, despite the difference in age (Fig. 2).

Adding a layer of complexity to this portrait is the mourning scene found on the verso: Back or reverse side of a double-sided object, such as a drawing or miniature., which features a woman standing beside a broken column—symbolizing a life cut short—and a weeping willow, a common symbol of grief, rebirth, and eternal life. These motifs likely indicate that the miniature was intended as a memorial portrait, though it remains unclear how they connect to the sitter. It may imply that the sitter was a different Mrs. Brummell who passed away prematurely around the time the miniature was realized, or it is possible that the miniature was reframed after the death of Mary Richardson Brummell in 1793 at the age of thirty-nine.

Whether this miniature depicts Mary Brummell or another Mrs. Brummell, the mourning scene on the verso imbues it with a sense of loss and remembrance. The sitter’s confident gaze, juxtaposed with the somber imagery on the reverse, reflects the delicate balance between personal identity and the emotions tied to memorialization. The work captures both the vibrant presence of the sitter and the poignant sense of a life touched by tragedy, while revealing insight about Smart’s process.

Notes

-

It is uncertain where the name Kendall came from; however, in an inventory sheet from the Starr family, the portrait is identified as #215, Miss Kendall, and dated 1784. Scans in NAMA curatorial files.

-

The miniature was also reproduced in a Nelson-Atkins publication, “Exhibitions: Portrait Miniatures by John Smart,” Gallery Events (December 1965). The exhibition was held in the Burnap Ceramics Room, December 10–January 2, 1965.

-

The interior inscription reads “Mrs. Brommell”; however, Smart’s other portrait is clearly entitled “Brummell,” and it is the same sitter.

-

Sotheby’s, London, “The Property of Dyson Perrins, Esq.,” May 14, 1959, lot 68.

-

Philip Carter, “Brummell, George Bryan [known as Beau Brummell] (1778–1840),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, January 6, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/3771.

-

Carter, “Brummell, George Bryan [known as Beau Brummell].”

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Lady (pencil drawing).

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 114, as Unknown Lady.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Mrs. Brummell, Probably Mary Brummell.

References

“Exhibitions: Portrait Miniatures by John Smart,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (December 1965): (repro.).

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 114, p. 41, (repro.), as Unknown Lady.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.