Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Self-Portrait, 1793,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1599.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Self-Portrait, 1793,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1599.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

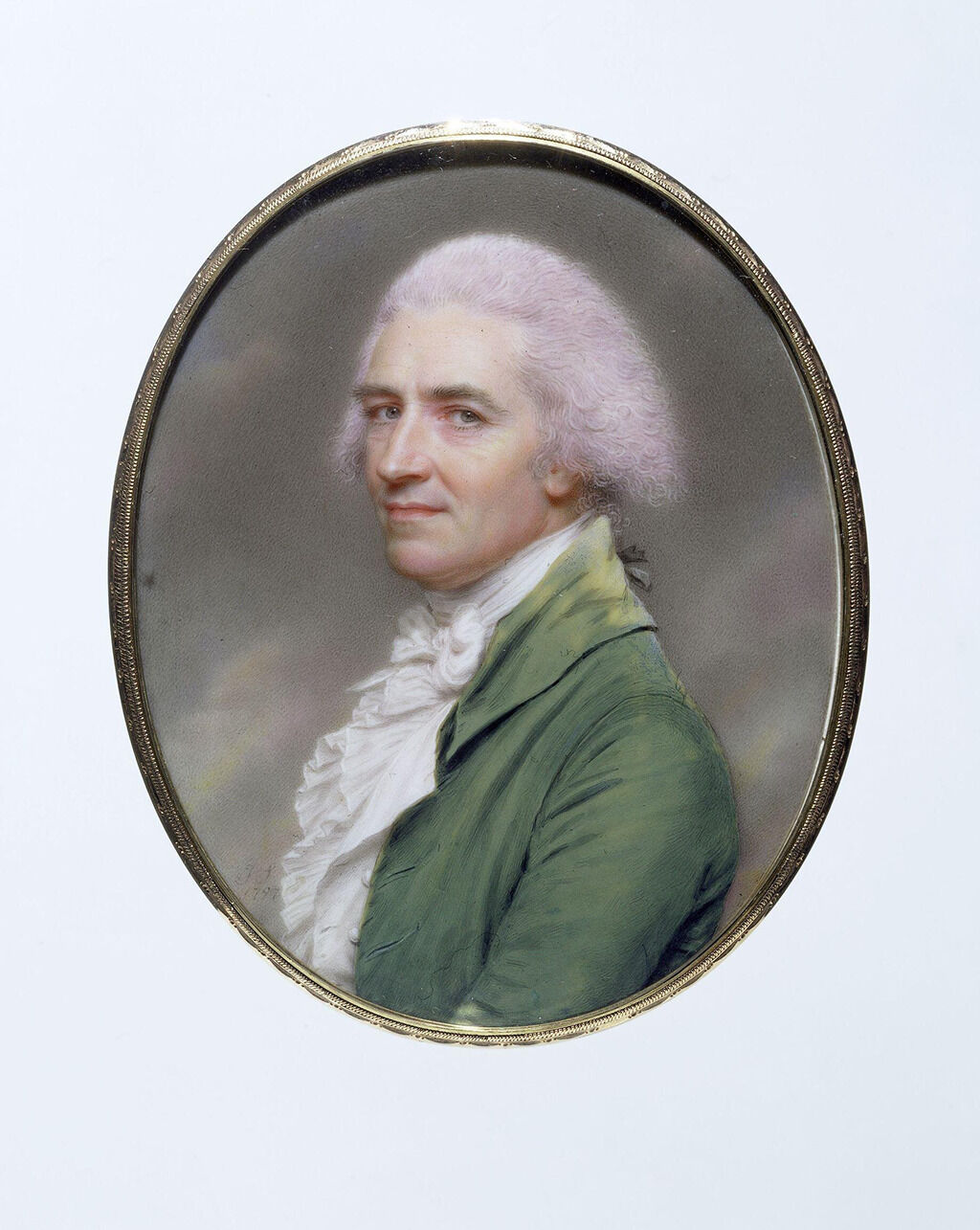

Martha Jane Phillips and John W. Starr assembled one of the most comprehensive collections of works by English artist John Smart, including signed and dated examples from nearly every year of the artist’s career. Despite their persistent efforts, acquiring a self-portrait remained elusive.1I am grateful to Starr Research Assistants Maggie Keenan, who provided much research support and the airtight provenance narrative for this object, and Blythe Sobol, whose meticulous search of correspondence between the Starr family and their network of miniature collectors, dealers, and colleagues was of immeasurable importance. In 1954, they learned of a potential self-portrait in private hands, but they were too late; it was sold to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Fig. 1).2In a series of letters between Martha Jane Starr to Cleveland Museum of Art curator Louise Burchfield, Starr asked if Burchfield was aware of any self-portraits by John Smart, as she wanted something special to mark their twenty-fifth anniversary; Martha Jane Starr to Louise Burchfield, August 18, 1954, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City. In Burchfield’s return letter of September 3, 1954, she mentioned a portrait held with a Smart descendant (through his daughter), the Reverend Howard Grindon, but she was unsure if he retained it. Grindon had offered it to Cleveland collector Edward B. Greene for $1,000, but Greene offered a low amount between $250 and $300; Grindon secured an offer from the MFA Boston for $750, and Greene was not interested in matching it. See Louise Burchfield to Martha Jane Starr, September 3, 1954, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection, a copy of which is in the NAMA curatorial files. Moreover, Greene likely already had a self-portrait, or was in the process of acquiring one, by 1952; see provenance entry for John Smart, Self-Portrait, in Cory Korkow and Jon L. Seydl, British Portrait Miniatures (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013), 156, cat. 34. The Starrs wrote Grindon on September 11, 1954, asking about the self-portrait, and he replied in a single sentence that he had completed a sale of the miniature to the MFA. See the Reverend Howard Grindon to Martha Jane and John Starr, September 11, 1954, NAMA curatorial files. Relentless in their pursuit, they appealed to successive Boston museum directors to sell or trade for the work, but they were unsuccessful.3The Starrs appealed to NAMA director Laurence Sickman to contact Boston on their behalf; see Martha Jane Starr to Laurence Sickman, June 19, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. Sickman then wrote to MFA director Merrill C. Rueppel at some point in 1974 (he wrote a memo to himself, June 10, 1974 outlining his ask) and received a response dated January 3, 1975, that Boston was not interested in a trade or sale; see memo from June 10, 1974, and return letter from Merrill C. Rueppel, January 3, 1975, NAMA curatorial files. The Starrs made a second appeal to Boston in 1981 via NAMA director Ross Taggart. Taggart wrote MFA director John Walsh Jr., perhaps thinking since the staffing had changed they could try again, and Boston responded with the possibility of a long-term loan of the self-portrait, which the museum did not pursue. See John Walsh Jr. to Ross Taggart, October 15, 1981, NAMA curatorial files. They ultimately acquired an oil painting of Smart by his near-contemporary Richard Brompton (English, 1734–1783), which they later donated to the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.4This was Mrs. Starr’s hometown museum. See Blythe Sobol, “A Few Choice Pieces: The History of the Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures,” in this catalogue. The Starrs’ quest for a self-portrait, initiated on their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, remained unrealized in their lifetime due to the rarity of such works.

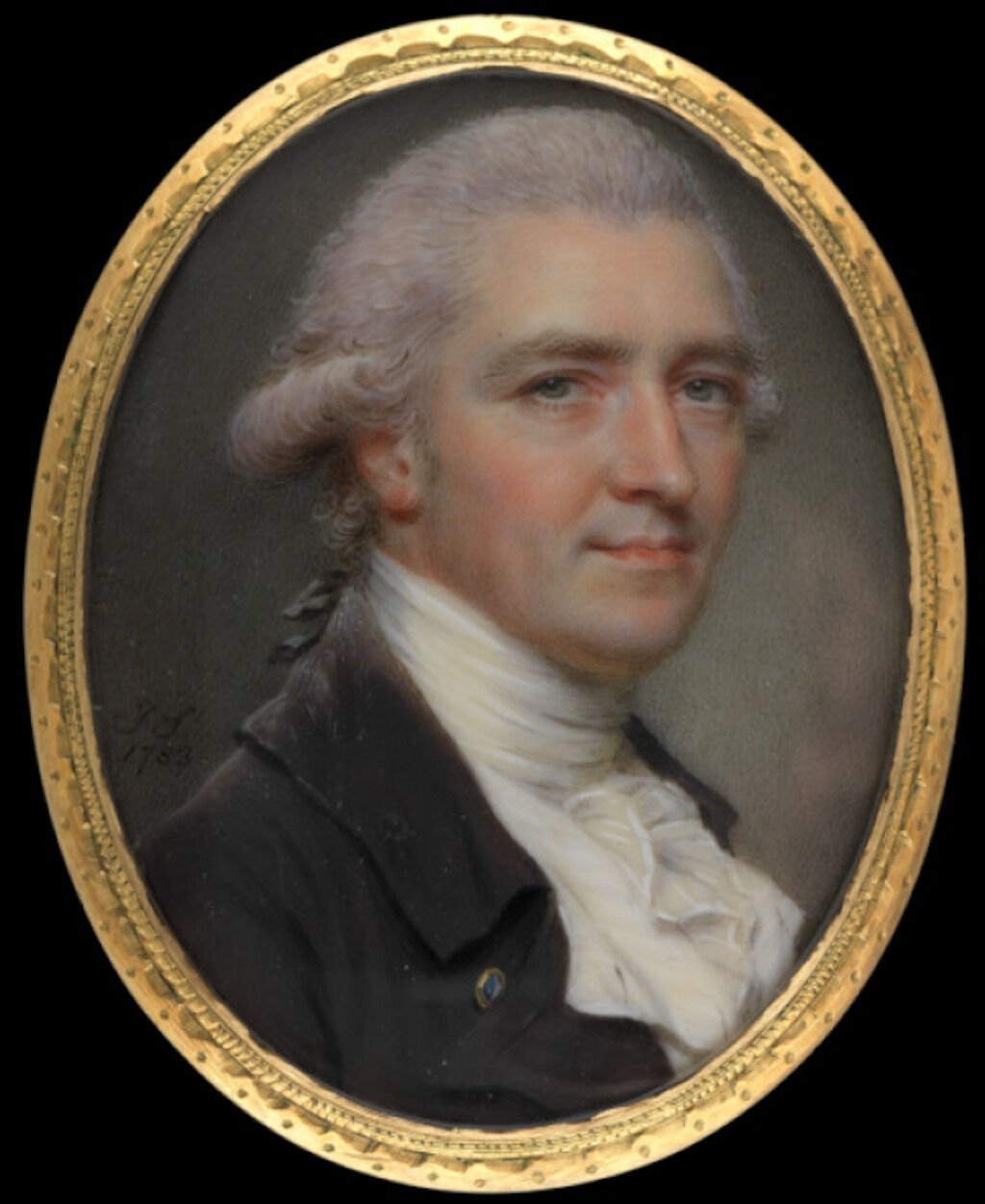

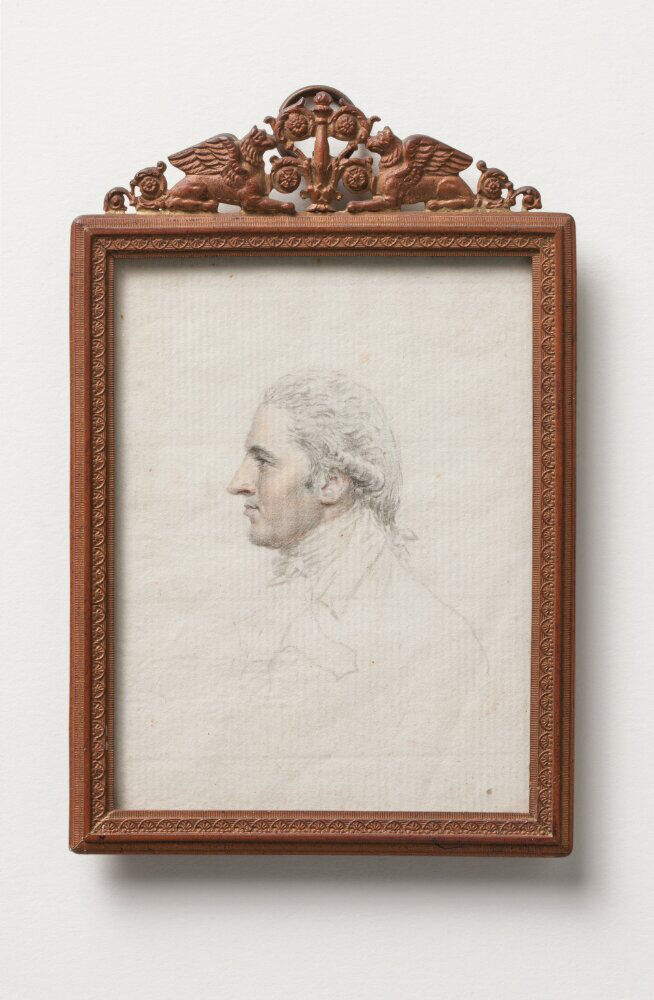

The Nelson-Atkins self-portrait is one of nine known examples by John Smart ranging in date from 1762 to 1810, the year before his death.5Daphne Foskett identified nine of these self-portraits in John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 73; however, she does not include their locations. Of these, six are watercolors on ivory, with three held in public collections—the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston (see Fig. 1); the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Fig. 2); and the Cleveland Museum of Art (Fig. 3)—and two in private collections, one of which was on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum (Fig. 4). The location of the 1810 portrait is currently unknown. The remaining three self-portraits are works on paper: an early pastel from 1762 (current location unknown), an unfinished drawing in the National Museum, Sweden (Fig. 5), and the present portrait.6See Foskett, John Smart, 73; and Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter, 1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,” Art Quarterly 17, no. 3 (Autumn 1954): 245, as Self-Portrait. The pastel—John Smart, Self-Portrait, 1762, pastel, exhibited at the Society of Artists, 1762, no. 103, as The First Attempt—is cited in Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter,” 252 (current location unknown). None of Smart’s contemporaries painted as many self-portraits (and there may be others yet untraced), suggesting a deliberate effort at self-promotion, highlighting Smart’s reputation as ambitious and self-confident.7The diarist Joseph Farington encountered Smart soon after he completed a portrait of William Henry West Betty (1806; Cincinnati Art Museum). Farington noted that “Smart was, as usual, very much delighted with his own performance.,” Joseph Farington, entry for May 11, 1806, The Diary of Joseph Farington, ed. Kathryn Cave (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 7:2757.

This portrait was completed in 1793 during Smart’s tenure in India (1785–1795), and the vivacity of its pose suggests he created it from life instead of copying it from an earlier work. His other Indian-period self-portrait (see Fig. 1), by contrast, looks comparatively stiff and also bears a remarkable resemblance to his portrait from around 1783 (see Fig. 4). The Nelson-Atkins portrait deviates from Smart’s typical forward-facing or three-quarters poses, presenting a dramatic profile of the fifty-two-year-old artist that accentuates his prominent nose and aged features.8This pose is reminiscent of an earlier, unfinished self-portrait at the Nationalmuseum, Sweden (see Fig. 4), as well as another work in the Starr collection, Portrait of John Holland, Governor of Madras. Known as “honest John” by his contemporary Richard Cosway (1742–1821), Smart portrays himself with crow’s feet, a creased forehead, a slack jaw, and a slight underbite, capturing an unvarnished likeness of his mature visage.9See George C. Williamson and Alyn Williams, How to Identify Portrait Miniatures (London: G. Bell, 1904), 135. The portrait’s size, slightly less than eight inches tall and seven inches wide, is also notable, making it the largest known self-portrait by Smart.10In contrast, the artist’s miniatures from the early 1790s typically measure around three inches tall. This, along with the artist’s inscription—“John Smart delineavit Seipsum, Madras. 1793” (John Smart drew himself, Madras, 1793)—suggests he considered it a significant standalone work.

While Smart often made pencil sketches as preparatory studies for his miniatures, the large scale of this self-portrait and its careful execution indicate it was intended as a finished composition. The exact purpose, however, remains speculative: it could have been an advertisement of his skills or a personal piece for his family. The timing aligns with a period when Smart created portraits of his daughter Sophia and her husband, Lt. John Dighton.11See John Smart, Portrait of Sophia Dighton, 1791, pencil, heightened with touches of white on laid paper, 6 5/8 x 5 5/8 in. (16.8 x 14.3 cm), in “Old Master and British Works on Paper,” Sotheby’s, London, July 8, 2021, lot 163, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/old-master-british-works-on-paper/portrait-of-sophia-dighton-1770-1793-the-artists; and John Smart, Portrait of Lt. John Dighton, 1791, graphite and brown wash on medium, moderately textured cream laid paper, sheet: 6 7/8 x 5 3/4 in. (17.5 x 14.6 cm), Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:7902. After Sophia’s death in 1793—the same year as this portrait—Smart returned to London with his grandson, while Sophia’s widower stayed in India. Dighton retained several family portraits, including this one, which may suggest the works were intended to be part of a lasting group of family portraits.12I am grateful to Maggie Keenan, who connected the timing of these portraits and made the suggestion that Smart could have been working on assembling a larger family group portrait. She feels this suggestion is supported, as all the portraits passed down the Dighton family line, which was an anomaly since most of Smart’s drawings passed through his son, John James Smart (1805–1870), and his descendants William Henry Bose (1875–1957), Lilian Dyer (1876–1955), and Mabel Annie Busteed (1878-1967), who sold their drawings in the 1930s. These works passed through the Dighton family, unlike most of Smart’s other drawings, which were inherited by his son and later descendants.

In 1981, the Dighton family’s collection, including this self-portrait, was sold at auction. German-Swiss collector Erika Pohl-Ströher (1919–2016) acquired at least three of these works, and they were sold again in her posthumous sale in 2020. The present self-portrait was acquired by a private London collector, who kept it until fall 2023, when it was consigned to a London dealer. With support from Starr family descendants, the museum acquired this remarkable work in the year marking John and Martha Jane Starr’s ninety-fifth wedding anniversary—a fitting tribute to their enduring legacy.

Notes

-

I am grateful to Starr Research Assistants Maggie Keenan, who provided much research support and the airtight provenance narrative for this object, and Blythe Sobol, whose meticulous search of correspondence between the Starr family and their network of miniature collectors, dealers, and colleagues was of immeasurable importance.

-

In a series of letters between Martha Jane Starr to Cleveland Museum of Art curator Louise Burchfield, Starr asked if Burchfield was aware of any self-portraits by John Smart, as she wanted something special to mark their twenty-fifth anniversary; Martha Jane Starr to Louise Burchfield, August 18, 1954, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City. In Burchfield’s return letter of September 3, 1954, she mentioned a portrait held with a Smart descendant (through his daughter), the Reverend Howard Grindon, but she was unsure if he retained it. Grindon had offered it to Cleveland collector Edward B. Greene for $1,000, but Greene offered a low amount between $250 and $300; Grindon secured an offer from the MFA Boston for $750, and Greene was not interested in matching it. See Louise Burchfield to Martha Jane Starr, September 3, 1954, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection, a copy of which is in the NAMA curatorial files. Moreover, Greene likely already had a self-portrait, or was in the process of acquiring one, by 1952; see provenance entry for John Smart, Self-Portrait, in Cory Korkow and Jon L. Seydl, British Portrait Miniatures (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013), 156, cat. 34. The Starrs wrote Grindon on September 11, 1954, asking about the self-portrait, and he replied in a single sentence that he had completed a sale of the miniature to the MFA. See the Reverend Howard Grindon to Martha Jane and John Starr, September 11, 1954, NAMA curatorial files.

-

The Starrs appealed to NAMA director Laurence Sickman to contact Boston on their behalf; see Martha Jane Starr to Laurence Sickman, June 19, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. Sickman then wrote to MFA director Merrill C. Rueppel at some point in 1974 (he wrote a memo to himself, June 10, 1974 outlining his ask) and received a response dated January 3, 1975, that Boston was not interested in a trade or sale; see memo from June 10, 1974, and return letter from Merrill C. Rueppel, January 3, 1975, NAMA curatorial files. The Starrs made a second appeal to Boston in 1981 via NAMA director Ross Taggart. Taggart wrote MFA director John Walsh Jr., perhaps thinking since the staffing had changed they could try again, and Boston responded with the possibility of a long-term loan of the self-portrait, which the museum did not pursue. See John Walsh Jr. to Ross Taggart, October 15, 1981, NAMA curatorial files.

-

This was Mrs. Starr’s hometown museum. See Blythe Sobol, “A Few Choice Pieces: The History of the Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures,” in this catalogue.

-

Daphne Foskett identified nine of these self-portraits in John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 73; however, she does not include their locations.

-

See Foskett, John Smart, 73; and Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter, 1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,” Art Quarterly 17, no. 3 (Autumn 1954): 245, as Self-Portrait. The pastel—John Smart, Self-Portrait, 1762, pastel, exhibited at the Society of Artists, 1762, no. 103, as The First Attempt—is cited in Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter,” 252 (current location unknown).

-

The diarist Joseph Farington encountered Smart soon after he completed a portrait of William Henry West Betty (1806; Cincinnati Art Museum). Farington noted that “Smart was, as usual, very much delighted with his own performance.” Joseph Farington, entry for May 11, 1806, The Diary of Joseph Farington, ed. Kathryn Cave (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 7:2757.

-

This pose is reminiscent of an earlier, unfinished self-portrait at the Nationalmuseum, Sweden (see Fig. 4), as well as another work in the Starr collection, Portrait of John Holland, Governor of Madras.

-

See George C. Williamson and Alyn Williams, How to Identify Portrait Miniatures (London: G. Bell, 1904), 135.

-

In contrast, the artist’s miniatures from the early 1790s typically measure around three inches tall.

-

See John Smart, Portrait of Sophia Dighton, 1791, pencil, heightened with touches of white on laid paper, 6 5/8 x 5 5/8 in. (16.8 x 14.3 cm), in “Old Master and British Works on Paper,” Sotheby’s, London, July 8, 2021, lot 163, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/old-master-british-works-on-paper/portrait-of-sophia-dighton-1770-1793-the-artists; and John Smart, Portrait of Lt. John Dighton, 1791, graphite and brown wash on medium, moderately textured cream laid paper, sheet: 6 7/8 x 5 3/4 in. (17.5 x 14.6 cm), Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:7902.

-

I am grateful to Maggie Keenan, who connected the timing of these portraits and made the suggestion that Smart could have been working on assembling a larger family group portrait. She feels this suggestion is supported, as all the portraits passed down the Dighton family line, which was an anomaly since most of Smart’s drawings passed through his son, John James Smart (1805–1870), and his descendants William Henry Bose (1875–1957), Lilian Dyer (1876–1955), and Mabel Annie Busteed (1878-1967), who sold their drawings in the 1930s.

Technical Note

The self-portrait is drawn on identical sheets of blued white, medium-thick, moderately textured laid paper: One of the two types of paper. Until the mass manufacture of paper began in the mid-eighteenth century, all paper was handmade and quite expensive, as the process was laborious. Linen, cotton, or hemp rags were soaked in vats and stirred until they disintegrated into pulp, which was pressed into a mold consisting of a wooden frame of gridded copper wires; the parallel laid wires were thinner and more closely spaced than the thicker, widely spaced chain wires. The linear impressions made by the laid wires formed what are called laid lines on the finished sheet of paper; the wider lines that cross them are called chain marks. In the late eighteenth century, there were widespread changes in the laid mold structure, and papers produced prior to this time are distinguishable by an accumulation of fibers along the chain lines. The other type of paper is wove paper.. With magnification, blue pigment particles are visible within the paper furnish: In paper making, furnish refers to the fibers that compose the paper as well as to the mixture of fibers and water that eventually form the paper sheet.. The sheets are laminated together with the mold side of the papers facing outward. The image side is twelve millimeters shorter than the backing paper. After the sheets were attached together, they were cut to an oval shape. There is no accumulation of paper fibers along the chain lines, indicating that the paper was formed on a mold that became available in the late eighteenth century. On the back is a partial watermark reading “TMAN,” suggesting that the sheet was made at a Whatman mill.

Provenance

John Smart (1741–1811), Madras, India, 1793;

To his son-in-law, John Dighton (1761–1840), Madras, India, and Gloucestershire, England, by 1795–1840 [1];

Possibly inherited by his sister, Lucy Machen (née Dighton, 1757–1855), Gloucestershire, 1840–1855 [2];

Possibly by descent to her son, Edward Machen (1783–1862), Gloucestershire, 1855–1862;

Possibly by descent to his son, Rev. Edward Machen (1817–1893), Gloucestershire, 1862–1893;

By descent to his son, Charles Edward Machen (1849–1917), Gloucestershire, 1893–1917 [3];

By descent to his son, Henry Arthur Ilbert Machen (1880–1958), Gloucestershire, 1917–1958 [4];

By descent to his children, James Edward Hugo Henry Machen (1910–1992) and Joan Hildegarde Sabine Machen (1912–2001), 1958–October 19, 1981;

Purchased from their sale, Silhouettes and Important Portrait Miniatures, Sotheby, Parke, Bernet, London, October 19, 1981, lot 184, as A Self-Portrait, by Dr. Erika Pohl-Ströher (1919–2016), Switzerland, 1981–2016 [5];

Purchased from Dr. Pohl-Ströher’s posthumous sale, Old Master Day Sale, Sotheby’s, London, July 29, 2020, lot 247, as Self-Portrait, by a private collector, London, 2020–2023;

With Lowell Libson and Jonny Yarker Ltd, London, 2023–2024;

Purchased from Lowell Libson and Jonny Yarker by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2024.

Notes

[1] It is possible that John Smart first gifted his daughter, Sophia Dighton (née Smart, 1768–1793), the drawing, but she died in Madras in the summer of 1793. Smart left for London in 1795, and John Dighton remained in Madras until around 1821.

[2] John Dighton’s sister, Lucy Machen (née Dighton), is his only sibling who outlived him.

[3] According to the October 19, 1981, sale, Charles Edward Machen had “4 children, including the father of the present owner of the Smart-Dighton portraits.”

[4] Henry Arthur Ilbert Machen had three other siblings: Charles Edward Machen died in his 20s or 30s with no known spouse or kids; Lucy Machen; and Lionel Machen, who immigrated to Australia in 1912. The description, “4 children, including the father” implies a son, not a daughter, so Lucy likely did not inherit the portrait. This suggests that Henry was the inheritor. This is confirmed by Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter—1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,” Art Quarterly 17, no. 3 (Autumn 1954): 252, which describes the 1793 Self-Portrait as in the “Collection of H. A. Matchen, Esq., Gloucestershire.”

[5] Lots 184–89 were listed as, “The property of a descendant of the Dighton family.” Lot 184 is described as, “A self-portrait, head and shoulders in profile to dexter, with hair en queue, pencil on paper, rectangular gilt gesso frame, oval 6 3/8 in.; 16.2 cm. This portrait would seem to have been executed at about the same period as the self-portrait illustrated by Foskett (D.), John Smart, 1964, pl. III, fig. 7, which is dated 1797, but it is likely that as it belongs to the group of portraits below, which were all painted in Madras between 1790 and 1792. It may be a few years earlier in date than this, and prior to his departure from India in 1795.” According to the attached price list, lot 184 sold for 3,300 pounds. The illustration shows a framed border around the self-portrait, which conceals the artist’s inscription, and therefore explains the work’s then-unknown date.

Exhibitions

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Self-Portrait.

References

Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter—1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,” Art Quarterly 17, no. 3 (Autumn 1954): 245, (repro.), as Self-Portrait.

Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 73.

Silhouettes and Important Portrait Miniatures (London: Sotheby, Parke, Bernet, October 19, 1981), 59, (repro.), as A Self-Portrait.

John Ingamells, National Portrait Gallery: Mid-Georgian Portraits 1760–1790 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2004), 438.

Old Master Day Sale (London: Sotheby’s, July 29, 2020), lot 247, as Self-Portrait.

“John Smart Portrait Miniatures Showcased at Nelson-Atkins,” ArtDaily (December 21, 2024): https://artdaily.cc/news/176685/John-Smart-portrait-miniatures-showcased-at-Nelson-Atkins, as Self-Portrait.

Julian Zugazagoitia and Laura Spencer. Director’s Highlights: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Celebrating 90 Years, ed. Kaitlyn Bunch (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), 225, (repro.).

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.