Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1526.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1526.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

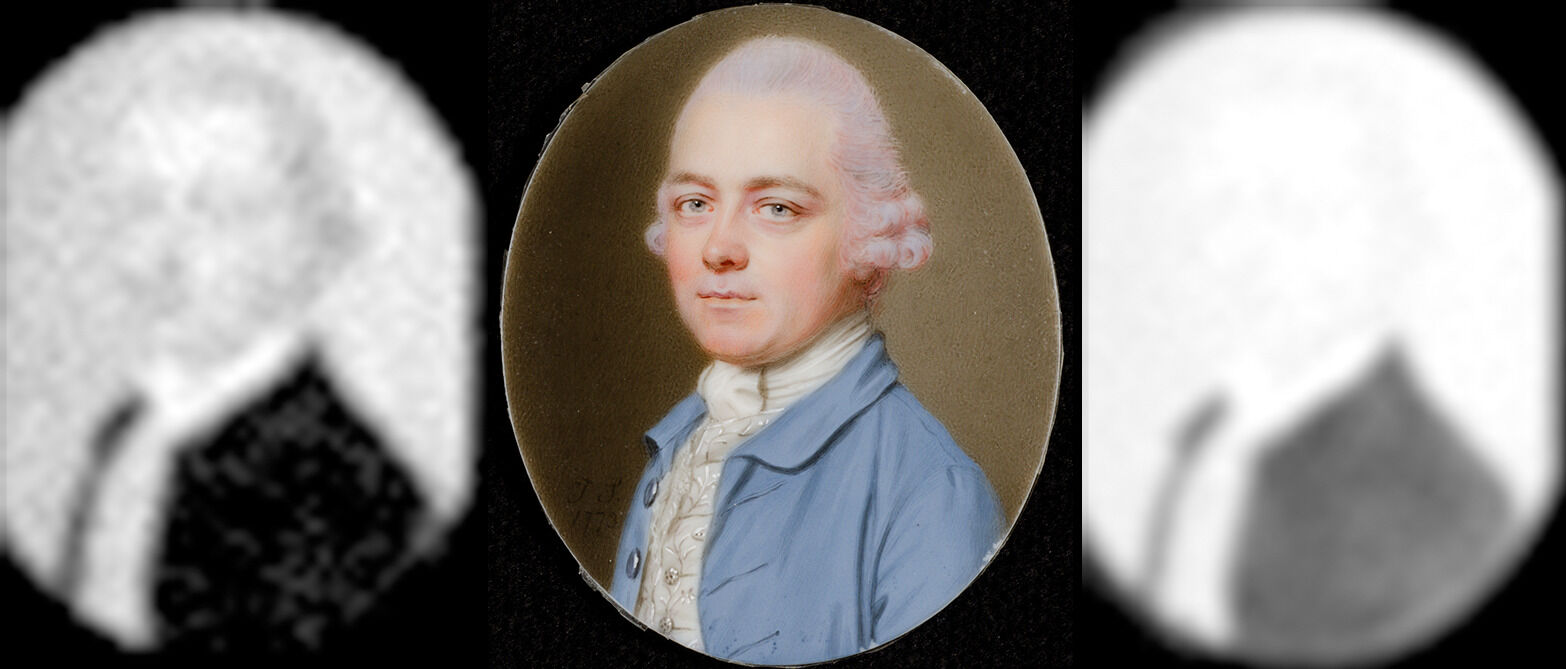

This unknown sitter is presented in a blue frock coat with a turned-down collar over a white embroidered waistcoat with a floral design. Beneath this, he wears a high-collared white shirt with a stock: A type of neckwear, often black or white, worn by men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. neatly tucked into the top of his waistcoat. While the sitter’s face is delicately flushed with a soft pink hue, it lacks the ruddy complexion seen in many of Smart’s later portraits. The date inscribed on the miniature is difficult to decipher but likely reads 1773, a conclusion supported by the cut of the man’s coat and the small scale of the work, which is typical of Smart’s miniatures from that period.

The sitter’s powdered hair, worn queue: The long curl of a wig., appears to have a pinkish-lilac tint. Although colored powder did exist at the time, its presence in portraiture is limited to miniatures and predominantly found in portraits produced by John Smart and artists in his immediate circle, whose clientele was largely made up of the merchant and military classes.1For more on this phenomenon in Smart’s work, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue. Although technical analysis conducted as part of the research for this catalogue confirmed that Smart used red iron rather than a fading lake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used.—suggesting the pink was a deliberate choice—Mellon scientist John Twilley posits that Smart may also have employed organic dye: A natural colorant made from complex organic compounds extracted from plants, animals, insects, lichens, and shellfish. As most natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore must be painted directly onto the surface. Organic dyes can be further processed and precipitated onto an inorganic substrate to produce a lake pigment. See also lake pigment..2See the accompanying technical entry by John Twilley and Stephanie Spence. These water-soluble dyes could have been mixed with the iron to create a more naturalistic brownish hue of hair that has since faded.3See the accompanying technical entry by John Twilley and Stephanie Spence. This alteration could account for the pinkish-lilac tones in the hair, suggesting that the effect is not a deliberate fashion statement but rather the result of color change over time.4The study of John Smart’s palette has been part of a Mellon Science Research project undertaken by John Twilley with the support of NAMA objects conservator Stephanie Spence. The research question grew out of the prevalence of pink hair among Smart’s sitters alongside the lack of pink hair among Smart’s contemporaries, other than those associated with his circle, in oil or miniature. This miniature was one of four examined as part of this discrete study, the results of which appear in the technical entry accompanying this curatorial entry. See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28; Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.

The bespoke suit this sitters wears signals his affluence. The intricate white embroidery and finely detailed floral pattern on the waistcoat reflect Smart’s meticulous attention to texture and ornamentation. The miniature is housed in a bracelet clasp, later converted into a locket, suggesting it was intended as a keepsake to be worn close to the heart—likely by a loved one. The sitter’s refined presentation and the intimate setting of the portrait underscore both his social status and the personal significance of this finely crafted miniature, which would have served as a cherished reminder of the sitter long after it was painted.

Notes

-

For more on this phenomenon in Smart’s work, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair.”

-

See the accompanying technical entry by John Twilley and Stephanie Spence.

-

See the accompanying technical entry by Twilley and Spence.

-

The study of John Smart’s palette has been part of a Mellon Science Research project undertaken by John Twilley with the support of NAMA objects conservator Stephanie Spence. The research question grew out of the prevalence of pink hair among Smart’s sitters alongside the lack of pink hair among Smart’s contemporaries, other than those associated with his circle, in oil or miniature. This miniature was one of four examined as part of this discrete study, the results of which appear in the technical entry accompanying this curatorial entry. See also Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28; Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Stephanie Spence and John Twilley, “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773,” technical entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1533.

MLA:

Spence, Stephanie, and John Twilley. “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773,” technical entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1533.

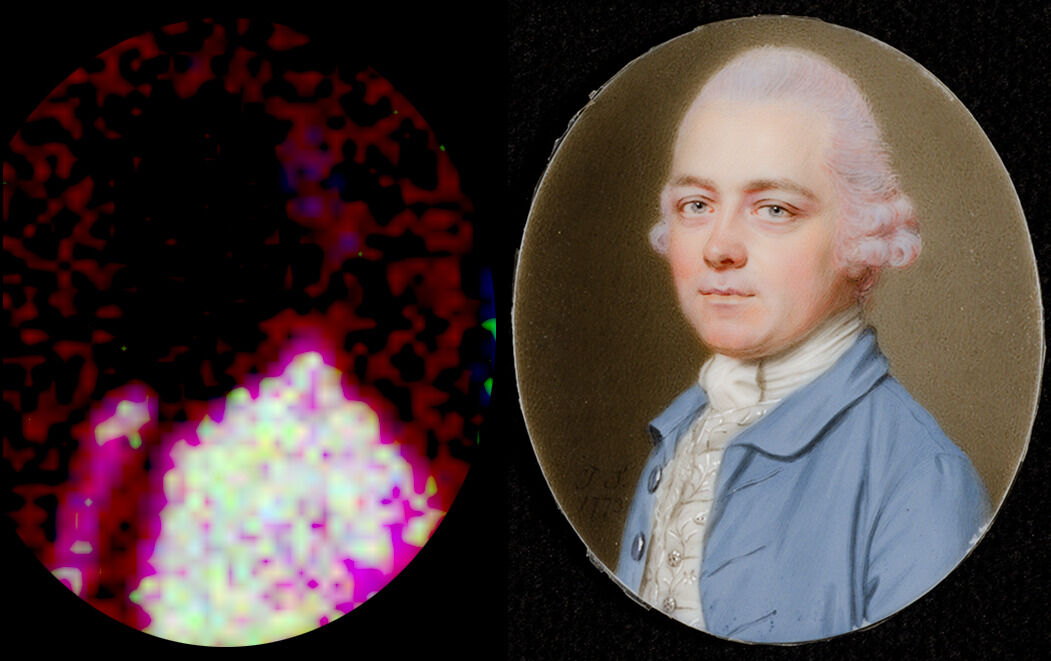

John Smart’s Portrait of a Man captures the likeness of an unidentified man with a combination of pink and lilac-tinted hair, dressed in a light blue frock coat, white waistcoat, and stock: A type of neckwear, often black or white, worn by men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.. The portrait is signed and dated “J.S. / 1773” in the lower left. The oval-shaped ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. measures just one and a half inches in height and is mounted in a simple gold case with glass covering. The case was originally designed to fit a bracelet but has since been converted to a locket.

The unusual color of the man’s hair is shared with eleven other sitters in the Nelson-Atkins collection as well as others in John Smart’s wider corpus outside the collection.1See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue. As Aimee Marcereau DeGalan has shown in her introductory essay, pink or lilac hair powder was uncommon in portraiture, with most subjects opting for white or grayish-white. However, Smart’s portraits of his merchant-class clientele reveal hints of pink and lilac hues, raising the question of whether this was a deliberate choice or the result of light-sensitive pigments fading over time, obscuring their original effect. Pigment analysis and technical imaging were performed on four John Smart portraits with light pink or lilac-tinted hair, spanning a twenty-five-year period of his career, to explore the artist’s palette and working techniques beyond the means of visual examination.2See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28; and Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.,3The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analysis was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

It is important to note that the very small scale and extreme thinness of the paint applications in portrait miniatures require that analysis be done, to the extent possible, through non-sampling means. However, no single analytical method provides a complete pigment analysis. Instead, pigment identification requires that information from different scientific techniques be combined and interpreted. This includes microanalytical methods that provide powerful means of extracting information from minute samples as small as single particles that cannot be obtained by non-sampling methods. Technical imaging alone cannot accurately identify materials but can be used as a complementary method to analytical techniques.4Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can identify restoration materials, such as inpainting and varnish coatings, as well as materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an artwork and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis. While these methods were used to find answers pertaining to the sitters’ hair color, they offer insights into the full compositions, revealing new information about John Smart’s palette and working techniques that were previously unknown.

Painted in watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. and gouache: Watercolor with added white pigment to increase the opacity of the colors. on ivory,5While it is likely that Smart used gouache in many of his miniatures, its presence has only been definitively confirmed in the four works that underwent technical analysis. this miniature portrait displays Smart’s technique of combining short, dense hatched: A technique using closely spaced parallel lines to create a shaded effect. When lines are placed at an angle to one another, the technique is called cross-hatching. and microscopic stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. while also utilizing areas of bare ivory for highlights to render the flesh tones. Shades of pink and brown were used in the hair and shading within the facial features. Shading around the man’s icy-blue eyes is a combination of magenta and brown. The deepest shadows around the nose and neck were created with translucent gray-brown and opaque red-brown colorants. Gradients of peach and pink make up the palette for the highlights and midtones. x-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of x-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method. reveals Smart’s use of iron earth pigments throughout the portrait (Table 1). A map for iron shows that the hair color and skin shadows, construction of the eyes, and other facial features employ iron earth pigments, such as ochers or siennas.

| Feature | Visible Color(s) | Inferred Partial Color Palette |

|---|---|---|

| Hair | Pink Blue White |

Iron oxide pigments Natural ultramarine* Tin oxide (white) Ivory support |

| Facial features | Red White |

Iron oxide pigments Tin oxide Ivory support |

| Coat | Blue White |

Smalt Copper blue/azurite Natural ultramarine Lead white |

| Waistcoat | Variations of white Gray |

Tin oxide Lead white Ivory support Carbon black** |

| Stock | White | Ivory support Lead white |

| Background | Brown White |

Iron oxide pigments Lead white |

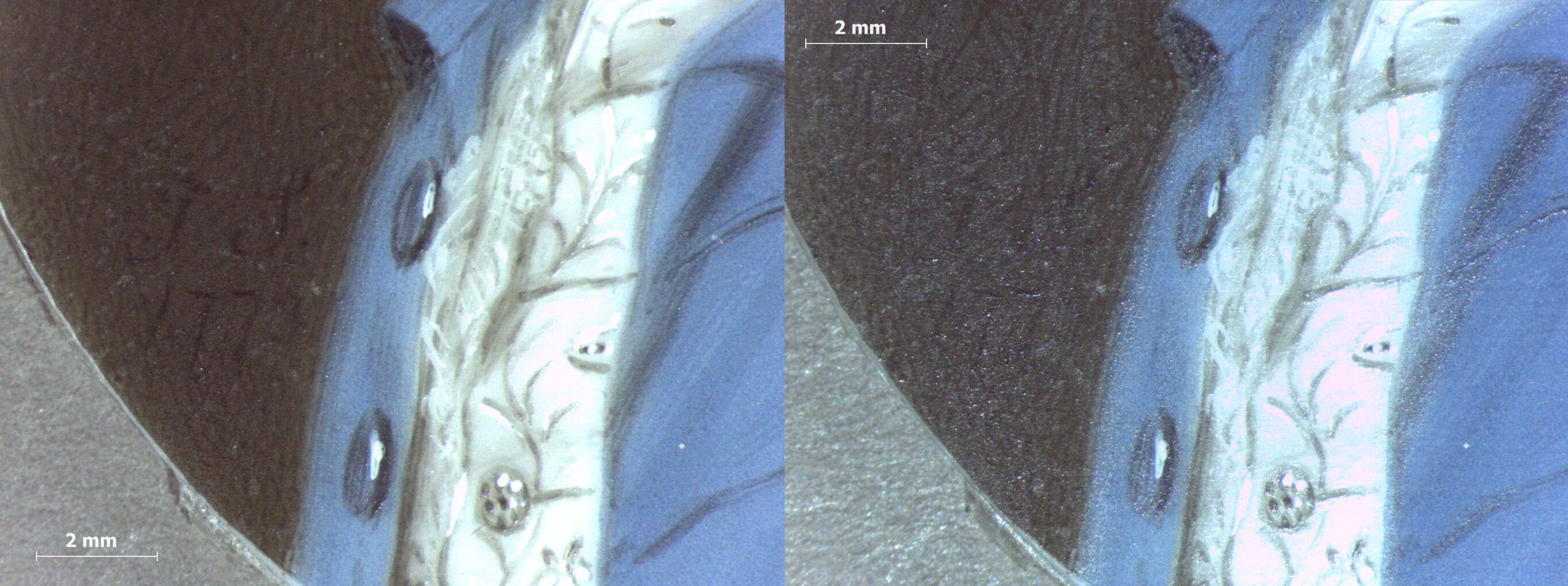

Smart used sgraffito: In Italian, meaning “scratched,” an art technique consisting of scratching through layers of paint. in several ways throughout the portrait, adding depth and texture to the sitter’s features. Narrow channels have been scratched into the paint around the lips, exploiting the translucent ivory for highlights. The sgraffito outline along the man’s fleshy jawline strengthens the contrast from the shadow below, while blunt scratches create wisps of hair to break up the boundary between the hairline and background.

The man’s powdered hair was executed by building up a combination of transparent colorants layer by layer to achieve the pink and lilac color (Fig. 1). While not evident elsewhere in the portrait, graphite lines are loosely sketched along the hairline and crown of the head, showing evidence of Smart’s preparatory drawing. Pink and gray-brown brushstrokes define the hair and side curls, giving the overall impression of pink hair. The subtle lilac tone was executed with a dilute wash of blue applied over the pink color. The blue wash makes heavier use of plant gum, with very little pigment; thus individual pigment particles scattered on the surface are visible. The lightest color appears to be bare ivory, with fine wisps of sgraffito in the side curls and along the crown of the head.

The saturation of the pink and gray-brown pigments gives the overall impression of pink hair color. However, Smart’s treatment of this sitter compared to the other male figure in Portrait of a Man, 1778 (F65-41/19) shows the subtle differences in the application of color in their hair. The lilac tone of F65-41/11 becomes more discernible in the side-by-side comparison of the two male portraits in both visible light and false-color infrared (FCIR): Images created through digital post-processing by combining and rearranging the color channels of visible and near-infrared images. In the visible image, the Red and Green channels are assigned to the Green and Blue channels respectively, while the infrared image is assigned to the Red channel. The false colors produced can aid in interpretation of media and materials present and inform further scientific analysis, conservation examination, and scholarly research. (Fig. 2a–d). In the FCIR images, the pink and lilac mixture in the hair of this male sitter presents as pink, while the pink hair of F65-41/19 presents as yellow, where the pigment mixture was found to contain only iron-based pigments and tin oxide. This visual difference in the false-color images of the male portraits is substantiated with elemental analysis where the pink false-color is indicative of ultramarine identified in the hair with scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDS): A combined technique that uses a scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy to analyze materials. Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an x-ray spectrometer so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting. and MA-XRF.6Pure ultramarine in gum arabic appears red in false-color IR. The pink tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is due to the pigment mixture that has been found to contain ultramarine and iron-based pigments. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the pigments that influence the false color appearance—explains why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007.

The only pigments found in the hair color were red iron oxide, lead white, and ultramarine, where the ultramarine was applied atop the pink mixture as a thin wash of blue particles. Light-induced fading of another light-sensitive colorant in the mixture, no longer discernible to the naked eye, could be a reason for the transformation of a natural hair color. Analysis of paint samples with SEM-EDS revealed no examples of alumina-based lakes, nor of lakes precipitated on any other compound. However, it remains possible that an organic dye: A natural colorant made from complex organic compounds extracted from plants, animals, insects, lichens, and shellfish. As most natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore must be painted directly onto the surface. Organic dyes can be further processed and precipitated onto an inorganic substrate to produce a lake pigment. See also lake pigment. with a yellow, green, or brown color, in soluble form rather than as a lake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used., was once present along with the surviving inorganic pigments to produce a more natural hair color.7Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped during MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was directed to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases in the SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

The lips were painted with two colors: deep magenta on the upper lip and a lighter peach color for the lower lip (Fig. 3). This dual lip color is a characteristic that has been observed on other Smart portraits in the Nelson-Atkins collection.8See the entire collection of miniatures by John Smart in this catalogue: https://nelson-atkins.org/starr/contents/Volume-4/John-Smart/. Thin lines of opaque red-brown pigment applied between the lips add further definition, followed by a final layer of clear glazing. A white highlight was added on the cleft, and bare ivory was used as a highlight along the lower lip line. Magenta hatching along the upper lip creates the faint appearance of a five o’clock shadow.

The sitter’s light blue coat was painted with an opaque application of blue and white paint with a textured, matte finish. Smart used a technique known as “floating” to float in the opaque mixture, leaving a level paint surface in which hatched shadows could be added with plant gum, either alone or in mixture with a small amount of pigment. Floating was a widely used method for painting men’s coats during the eighteenth century, where the textural quality of the matte gouache contrasted with the transparency of the facial features and background.9John Murdoch et al., The English Miniature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 20.

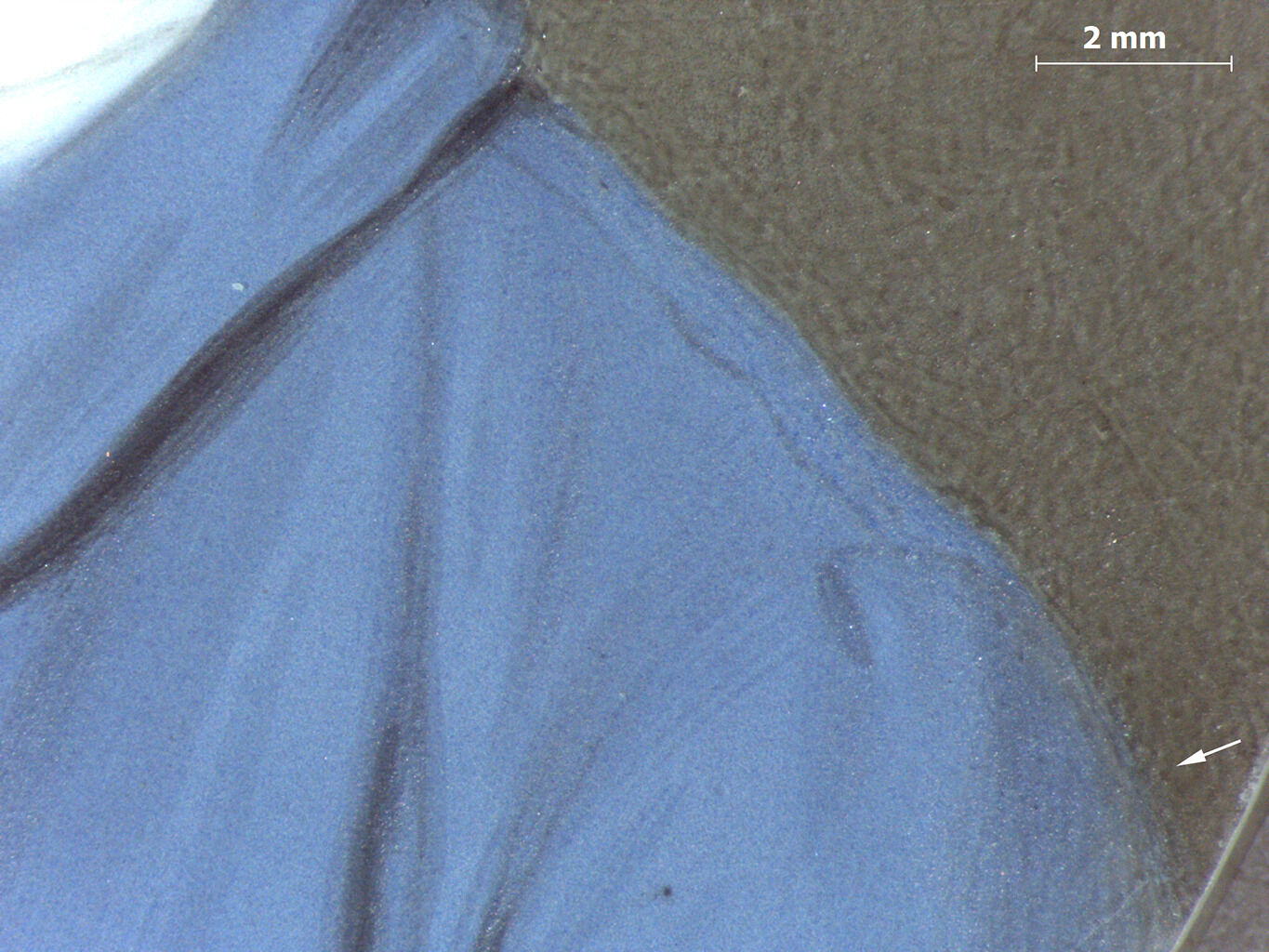

While literature calls out the use of a gum arabic: Derived from the sap of the African acacia tree, gum arabic was commonly used to bind watercolor pigments with water. In addition to its use as a binder, miniaturists capitalized on its glossy effect to create areas of highlight with larger quantities of gum. As with ivory, its availability benefited from trade routes that were expanding due to colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade. solution alone to create hatched shadows that saturate and darken the matte gouache, this portrait seems to rely on plant gum in mixture with pigment. Under normal illumination, the drapery and shadows match the matte appearance of the blue coat. This behavior contrasts with that of the other male portrait in this study, F65-41/19, in which the shading has a glossier appearance, suggesting the use of a heavier application of plant gum that provides greater saturation and gloss. Here, the hatched midtones present as a matte, medium blue color. The darker midtones appear to have some black added to the mixture, while the darkest shadows read as matte black. A raking-light detail of the coat reveals subtle variations in the treatment of the drapery, showing a slight glossy finish in the blacks and a matte finish in the blue midtones (Fig. 4a,b). The two blue buttons show a similar treatment in the shading with the addition of highlights painted with white impasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges.. A pentimento: From the Italian for “repentance,” a pentimento or pentiment, plural pentimenti, is an area revealing an element of the composition that has been moved or removed from the final composition. This is typically seen in underdrawing or elements hidden beneath added layers of paint, called overpaint. Pentimenti can be revealed by thinning layers of paint over time, or through the course of technical analysis with methods like x-radiographs or infrared reflectography. is visible along the man’s left arm where the composition was adjusted to widen the sleeve, and the brown background has become visible as the painting has aged (Fig. 5).

Maps for cobalt, copper, silicon, and potassium demonstrate that the blue jacket is a complex blend of a copper blue, ultramarine (containing sulfur), and smalt (which contains cobalt, silicon, and potassium). This use of three distinct blue pigments in the same painting is notable, even among Smart’s exquisitely detailed works (Fig. 6). Of the two white pigments that were discovered by XRF in this portrait, the map for lead reveals that the opaque quality of the gouache mixture was achieved by the addition of lead white. While lead white is prevalent in the blue coat, it is absent from the stock, face, and background.

The waistcoat is embroidered with a floral pattern of white and gray. The waistcoat and stock both make use of bare ivory for the base color. Opaque white highlights in the stock were thinly painted, while impasto was used to create the embroidery of the waistcoat. Tin, from tin oxide, is represented in the hair, at bright points accenting the waistcoat, and unevenly around the chin. Gray and brown colorants were used for outlines and shading in both the waistcoat and stock.

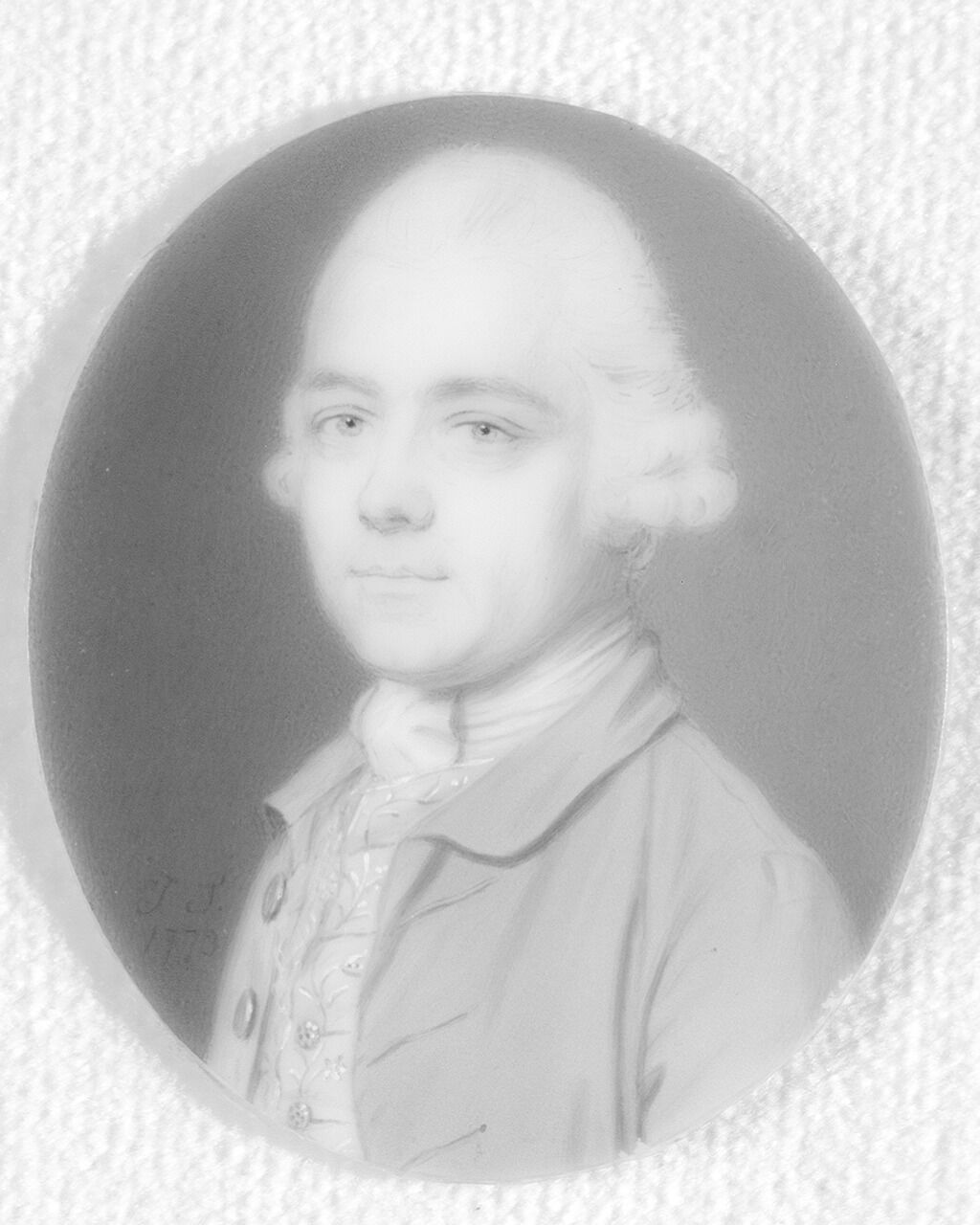

Carbon-based pigments, such as carbon black, are not identifiable with the analytical techniques described above but play a relevant role in this portrait. Dark areas in the infrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700–1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR-blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. image of this portrait correlate to areas of dark shading in the face, clothing, and signature, where carbon black pigments were added to the paint mixture (Fig. 7). Graphite (a form of carbon black) from the preliminary sketch around the sitter’s face is also visible in the infrared image.

The olive-brown background was painted with dense hatching and stippling. The background is a darker, more solidly applied color to the sitter’s right. XRF shows that the background is also heavily dependent on iron pigments, with the iron content varying from left to right. The direction of the individual brushstrokes follows the outline of the figure, indicating that the background was painted after the figure was completed.

Analytical results from the four portraits tested demonstrate that Smart’s technique varied with the gender of the sitter. The women (F65-41/28 and F65-41/39), whose fair complexions rely more heavily on the whiteness and translucence of the ivory support, are much more thinly painted than the men (F65-41/11 and F65-41/19), whose ruddy complexions required a heavier paint application on the ivory. This difference also extends to the representations of clothing and becomes apparent in MA-XRF elemental mapping, where the stronger response from the heavier paint of the male portraits contains more information on minor components in the mixtures.

All portraits give strong maps for calcium and phosphorous, the two primary elements of bone, tooth enamel, and ivory. Brighter areas in the maps indicate where the responses of these elements are not suppressed by overlying paint applications. In the two male portraits, the weak phosphorous response is blocked by heavy paint applications in the clothing. With this portrait the dark area of the elemental maps correlates to the thick paint application in the blue coat (Fig. 8). In contrast, the stock and waistcoat appear very bright, especially in the phosphorous map, revealing the extent that the bare ivory plays a role in portions of the clothing.

The paint surface has several losses around the perimeter of the ivory support. The largest along the bottom of the blue frock coat remain mostly obscured by the edge of the case. Heavy mold on the paint surface was removed during conservation treatment, allowing the date to be clarified as 1773 rather than 1770.10This miniature was dated to 1770 in the 1971 Starr collection catalogue. Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 96, p. 37. The date changed periodically until 2021, when the miniature was conserved.

The results of analyses of this corpus of John Smart miniatures extend beyond the peculiarity of the sitters with light pink and lilac-tinted hair, revealing previously unknown information about Smart’s palette. Comparisons of the four portraits spanning a twenty-five-year period of Smart’s career both in London and India have brought to light ways in which he innovated beyond methods described in contemporaneous painting treatises. Additionally, they illuminate pronounced differences in his approach to representation of male and female sitters. While the analyses do not reveal the use of lake pigments in the hair and fail to account for a color change, the possibility remains that now-faded organic dyes, not detectable by the methods available to the authors, could account for a color change. XRF elemental mapping used in conjunction with SEM-based elemental analysis has provided pigment identifications for part of the palette. Complementary information from additional analytical steps holds the potential for a comprehensive understanding of John Smart’s palette to be derived from the extensive holdings of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Notes

-

See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue.

-

See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28; and Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798, F65-41/39.

-

The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analysis was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can identify restoration materials, such as inpainting and varnish coatings, as well as materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an artwork and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis.

-

While it is likely that Smart used gouache in many of his miniatures, its presence has only been definitively confirmed in the four works that underwent technical analysis.

-

Pure ultramarine in gum arabic appears red in false-color IR. The pink tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is due to the pigment mixture that has been found to contain ultramarine and iron-based pigments. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the pigments that influence the false-color appearance—explains why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007.

-

Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped during MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was directed to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases in the SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

-

See the entire collection of miniatures by John Smart in volume 4 of this catalogue: https://nelson-atkins.org/starr/contents/Volume-4/John-Smart/.

-

John Murdoch et al., The English Miniature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 20.

-

This miniature was dated to 1770 in the 1971 Starr collection catalogue. Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 96, p. 37. The date changed periodically until 2021, when the miniature was conserved.

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1965;

Their gift through the Starr Foundation to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Gentleman.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 96, as Unknown Man.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of a Man.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 96, p. 37, (repro.), as Unknown Man.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.